Todd is president and owner of Todd Buck Illustration, Inc.

Todd Buck

Since 1990, his studio has been creating high quality custom medical and scientific illustrations for medical journals, pharmaceutical advertising and marketing, medical and consumer publishing, and patient education media. He is also Associate Professor of Illustration in the School of Art and Design at Northern Illinois University. He received a Masters Degree in Medical Illustration from the University of Illinois at Chicago Department of Biomedical Visualization and a BA in Biological Premedical Illustration from Iowa State University.

Todd is a Fellow of the Association of Medical Illustrators (AMI), has served on the AMI Board of Governors, and has presented workshops at the AMI conference. His illustrations have won awards from the AMI Salon, RxClub, DESI, Art Directors Club of NJ, and Creativity 26. Todd’s illustrations have been displayed at Chicago’s International Museum of Surgical Sciences, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the National Library of Medicine in Maryland, The Universidad Andres Bello in Santiago, Chile, and the Hong Kong Science Museum.

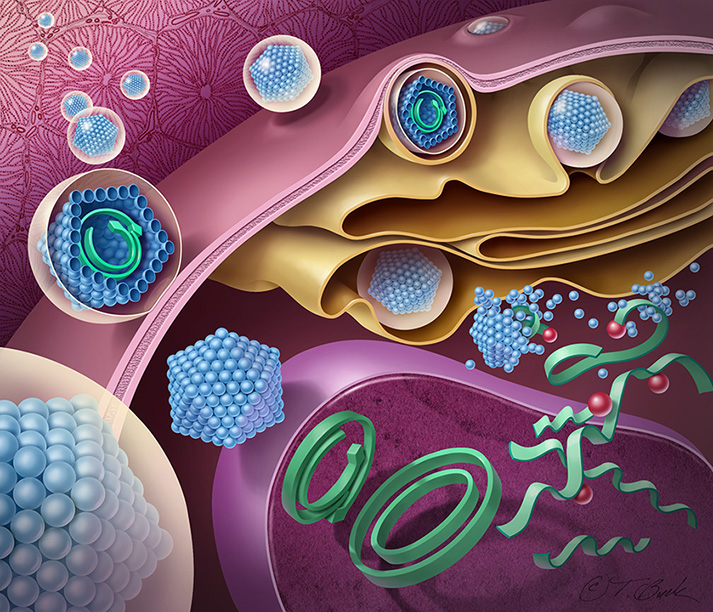

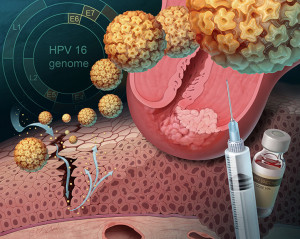

Human Papilloma Virus and Cervical Cancer

How did you come to choose medical illustration as your profession?

To me, the most powerful artistic influence is Mother Nature and inspiration lies in discovery. I think it is a natural tendency to study and try to understand what we proclaim to love.

I grew up as an outdoor kid and developed an affection for nature. I liked to draw flora and fauna, bringing specimens to the dining room table to draw. At 13 years old I started doing fish taxidermy at that same table. It was, and remains, a fascination with the natural world and an attempt to understand how it works, how everything is related, from molecules and cells to organisms to biocommunities to our dynamic earth and constellations and beyond. I started college at Iowa State University studying biology with the intent of becoming a high school biology teacher. However, I created many drawings on my class and lab notes to help me understand and remember the information. It was serendipitous that ISU had just a few years earlier started an undergraduate program that combines art and science in a degree called Biological Premedical Illustration (BPMI). The day my advisor explained it to me was the day my career path changed. As an undergraduate I created illustrations of various critters from dissections for publication in a zoology lab manual and worked part time in the Biocommunications Department at the ISU Veterinary College. From there I jumped to graduate school at the University of Illinois Department of Biomedical Visualization, then started my own business. Now, every project I work on is an opportunity to gain a better understanding of some scientific or medical concept, function, cause and effect, or method of action and help others understand it through my illustrations.

What is the extent of your medical background?

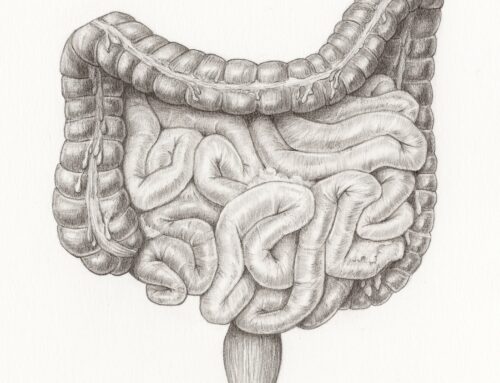

In graduate school we had courses with medical students, such as gross anatomy, pathophysiology, embryology, and histology. We also had a surgical illustration course where we attended surgeries, illustrated the procedures, and learned the protocol of an OR. The Association of Medical Illustrators offers continuing education workshops in a variety of medical and science based topics at their annual conference. We have many opportunities for direct collaboration with scientists, physicians, and surgeons to help illustrate their newest discoveries. It is important, given the diversity of projects medical illustrators are asked to work on, that we have enough medical and scientific knowledge to be able to understand and communicate with experts in a variety of medical and scientific areas. This is what sets us apart from other professional illustrators.

What was the hardest science class you took in graduate school? Did you study biochemistry?

I would have to say gross anatomy only because of the volume of information that needed to be committed to memory. It seems kind of silly to think that now, because after years in the field it seems I have thoroughly studied every area of the body for one project or another and the class would be much easier now. I took biochemistry and organic chemistry as an undergraduate. I do tell students interested in medical illustration how important the chemistry classes are. Much of the current research and methods of action are at this level.

How much research generally goes into a project?

The short answer is, as much as it takes. My illustrations are only as effective as my understanding of what I am illustrating. Each project is different in complexity, so I might understand it immediately and be able to visualize the story quickly, or it might be hours or days of study. I enjoy the science that requires me to stretch beyond what I already know.

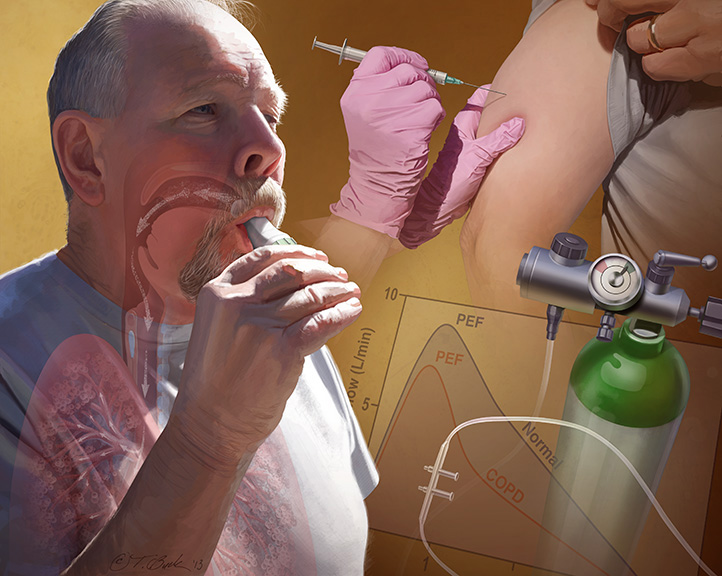

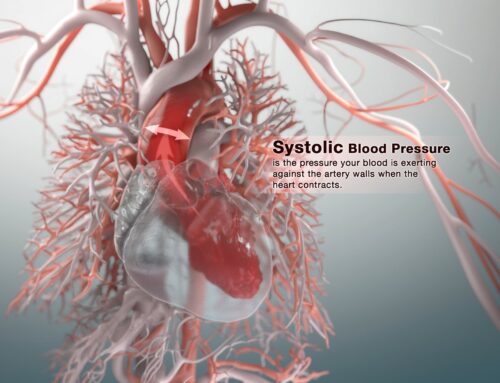

Scientific visualization combines hard science with artistic imagination. How do you decide what the microscopic world looks like?

There are many tools available and still being developed to help give form to objects we cannot see with the naked eye. Histological slides and electron microscopy are very helpful when trying to visualize and create accurate cellular environments. Sources developed by scientists to help visualize molecular structures, such as Protein Data Bank, are available for reference as well. They are still visual representations of microstructures based on current technology and research, which is as much a frontier of science as outer space exploration. Often medical illustrators have to take artistic license to create a visual that best explains a process or tells the intended story.

What is your favorite type of assignment?

My favorite type of assignments and the work I am most proud of are the ones in which I get to collaborate directly with science or medical experts and am the first to visually describe their research so that others may understand it. It is exciting to be on that front edge of discovery and scientific advancement. However, I very much like the variety of assignments that come into the studio. One week I may be illustrating how antiepileptic drugs work, the next I may be working on illustrations of nasal reconstruction surgery for an atlas, and the next I may be airbrushing large resin models for a health museum.

Have you become desensitized over the years to graphic imagery and concepts?

If the imagery is for educational purposes, such as a surgical procedure or a dissection, it does not usually bother me. And I have illustrated all the naughty bits more than once. Even so, graphic horror movies still gross me out.

How do you describe your craft to other people?

I tell them I use visual media to advance science and healthcare education, research, and understanding. Medical illustrators serve as visual translators between expert and novice, scholar and student, physician and patient. Or, to keep it light, I say, “I get to learn the science and then create art to help explain it.”

Has your career turned out as you had expected? What are the biggest changes that you have seen in the profession in the past several years (aside from the digital revolution)?

In graduate school, over 20 years ago, I wrote down my professional goals and a business plan for starting my own company and it worked out pretty much as planned. The biggest deviation from the original plan is I also became an Associate Professor of Illustration at Northern Illinois University.

Some of the biggest changes I see are the level of research and advancements made in visualizing subcellular and molecular details, the publishing industry switching to more digital formats, the challenge to protect copyrighted images once they are on the internet, the use of gaming in education, and constant software advancements for creating 2D and 3D imagery. The idea of visually communicating a message is the one constant. How it is done is taking on many formats.

What advice would you give to someone considering medical illustration as a career?

Make sure you are in love with science as much, if not more, than art and be willing to embrace technology. Of course, we all want the visuals to be beautiful, but the message or story or concept must be clear and accurate first.

If you weren’t a medical illustrator what would you be?

If I were not creating art of some sort or studying science, I’d be a bicycle tour guide. It would still include being exposed to nature and discovering new things. My heart soars when I am outdoors.

Todd Buck: Website // Medical Illustration Sourcebook portfolio

Featured Illustration: Human Papilloma Virus and Cervical Cancer