Plant Evolution is complicated, and in this blog I plan on simplifying it and trying to share some of the awe and joy that I get from the kindgom of plants. All the information is based an an excellent talk I recently heard on the subject, by Chris Thorogood and hosted by Julia Trickey.

Plants have been on this planet for more than 500 million years, first appearing as red seaweeds and diversifying into the plethora of forms and species we share our planet with today.

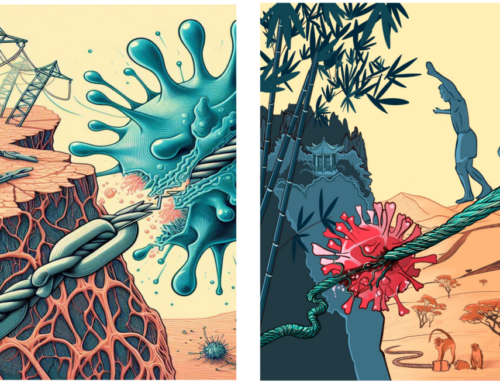

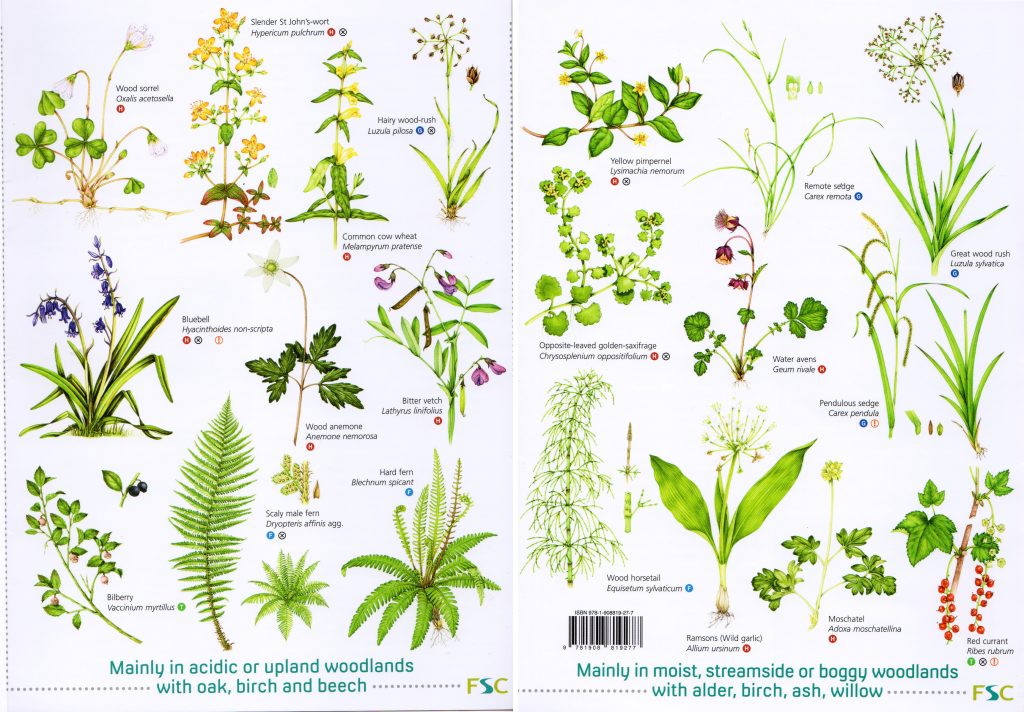

FSC Guide to Ancient Woodland plants I illustrated showing a whole range of plants

Plant Evolution time line: Non-flowering plants

If we follow a time-line, we can have some idea of the course of plant evolution on earth.

Let’s start way way back, in the Ordovician, about 500 million years ago. Nothing grew on land, but in the oceans algae, which we recognize as red seaweeds were growing. Green plants evolved from these, and adapted into more algaes and plants we still have today, like the Charophytes.

Jump to 470 million years ago, the Silurian. Plants have colonized land! They still need water for reproduction, and can’t grow to enormous sizes, but the green takeover has begun. In this time we see the emergence of Bryophytes: Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts.

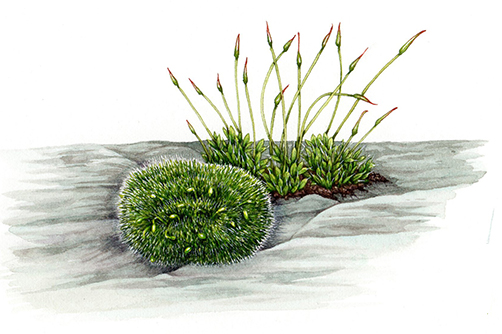

Grimmina pulvinata and Tortula muralis

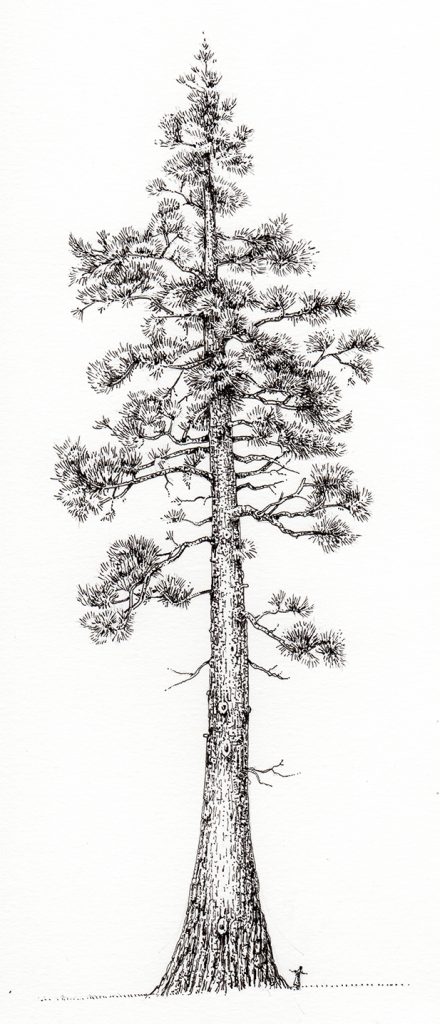

The next enormous milestone in plant evolution is the development of vascular tissue. Plants are now able to grow tall, creating forests. Clubmosses (or Lycopods, they’re not mosses at all) now emerge in the fossil record, about 350 million years ago. Lycopods now are small plants, but at their peak they could grow into trees up to 30m tall.

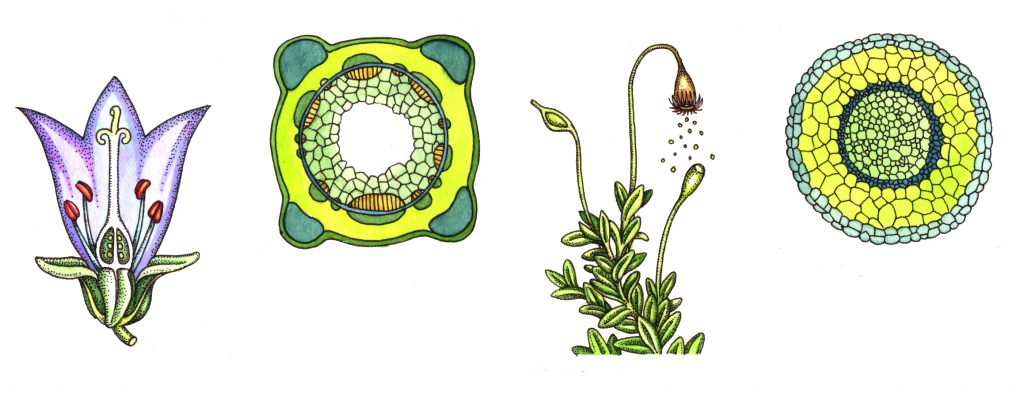

Vascular vs non vascular plants diagram showing cross section of the stem with vascular bundles

Ferns and Horsetails emerge next. Enormous tree ferns change the land, shading out the bryophytes. Even today, tree ferns can be enormous, and back in the Carboniferous they could grow to gigantic sizes. They still need water for spore dispersal, but are able to colonise drier habitats.

Plant Evolution time line: Seed producing plants

A massive change occurs; the seed evolves. This is, as Chris Thorogood puts is, “a little plant within a box”. Suddenly plants can live in dry environments. They can live as dormant seeds for years.

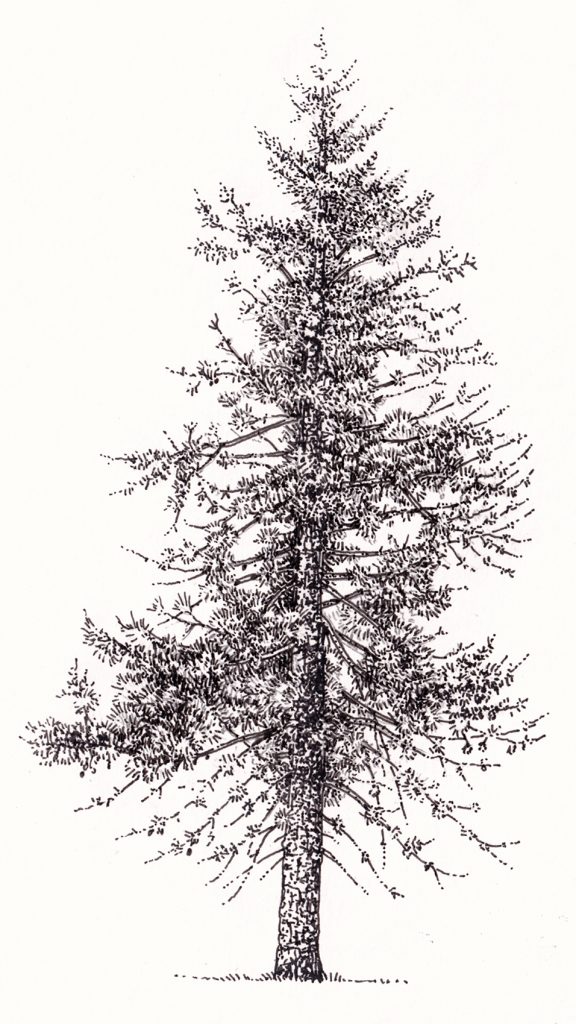

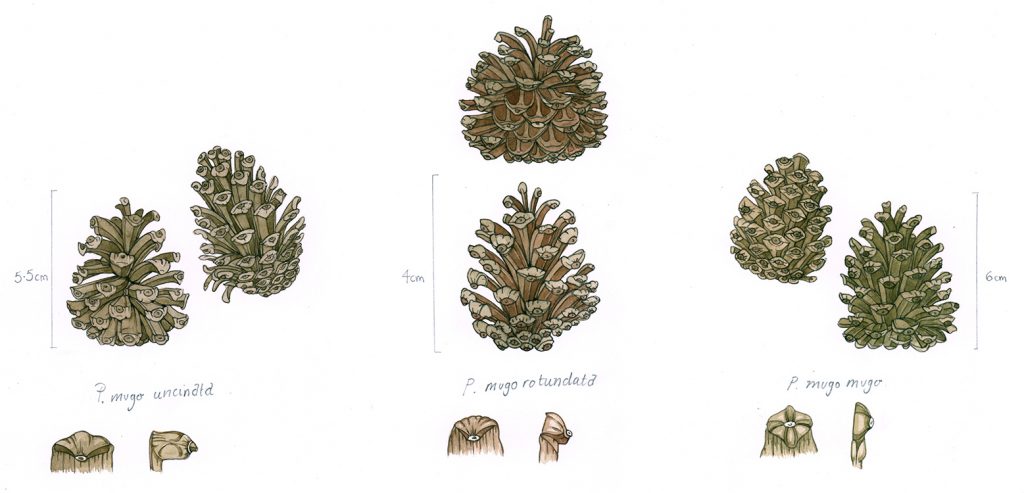

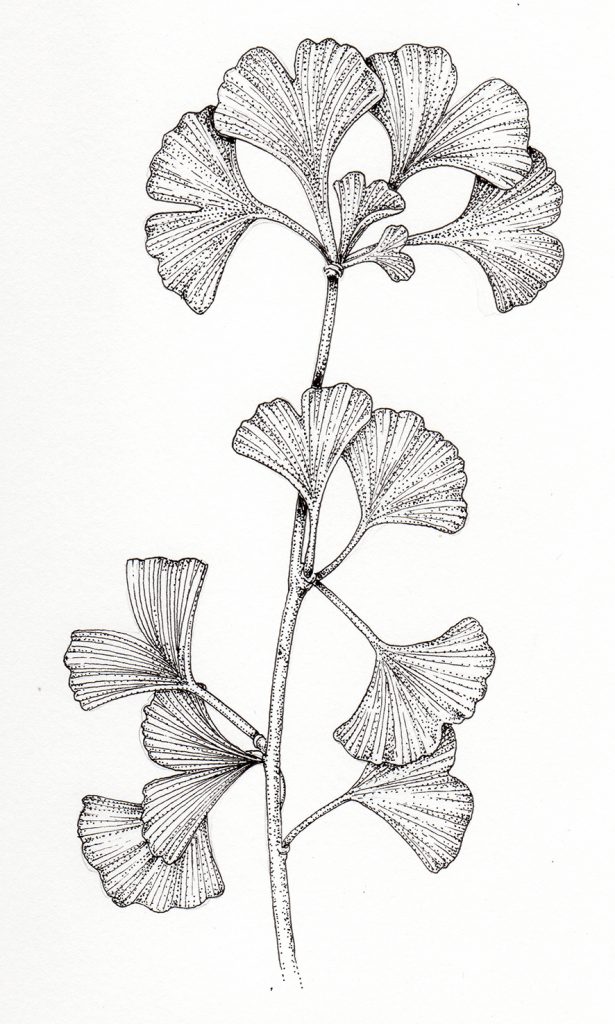

Gymnosperms; the conifers, cycads, and ginko appear around 320 million years ago, in the Permian. Their seeds aren’t enclosed in a fruit, but in cones.

Jack Pine Pinus banksia tree

Jump forward to the Triassic and Jurassic 280 million years ago, and the Cycads are in the ascendency.

Plant Evolution time line: Flowering plants

No-one knows quite when, but around 130 to 100 million years ago something extraordinary happens. Flowering plants appear in the fossil record. With tough seeds, flowers for pollinators, and the ability to exploit almost every habitat on earth; these take over. These comprise Magnoliids, Paleoherbs, Monocots and Eudicots. And they take over the planet, remaining dominant to this very day.

Plant evolution: Red algae

Red algae are marine seaweeds. It’s a bit of a catch-all phrase and covers most of the red seaweeds, unicellar and multi-cellular organisms. Brown seaweeds are a little different, and are thought to have evolved through endosymbiosis with red algae. A common red algae is Dulse, which is also edible.

Dulse Palmaria palmata

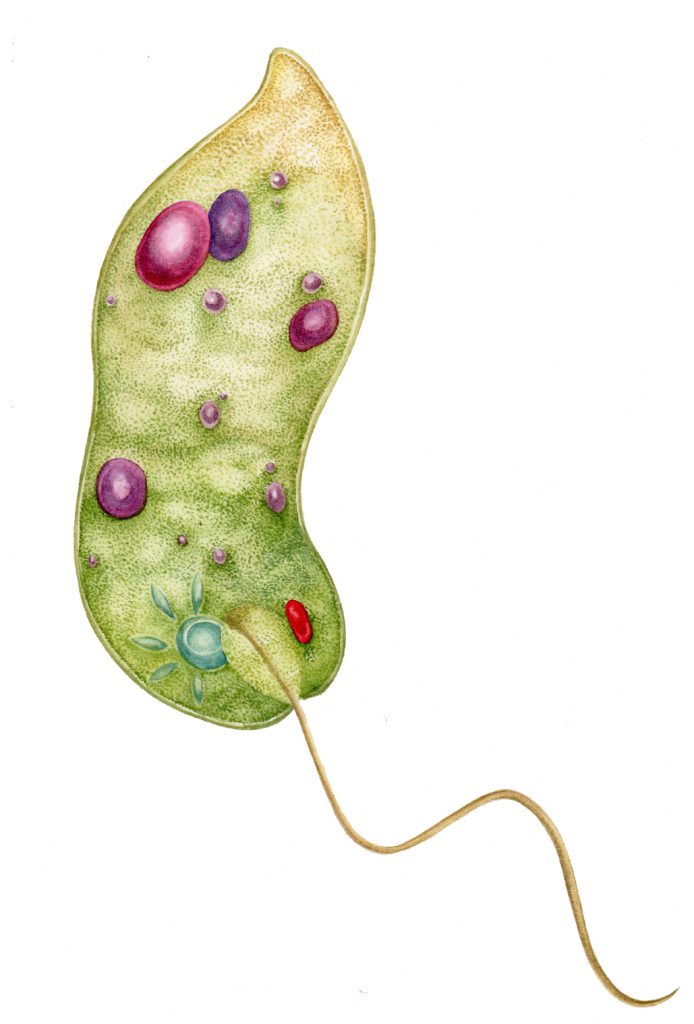

Plant evolution: Green algae and Charophytes

On a microscopic level, tiny green algae can be stunning. Many, like Desmids, are unicellular. Take a look at this film of Volvox (some Volvox are unicellular whilst others live colonially) or photos of Pediastrum, a green algae living in colonies

Some green algae are larger, forming mats in ponds and pools.

Charophytes appear in this group, and are considered the oldest living relatives of land plants. They pop up in the fossil record 500 million years ago and have remained unchanged until now.

Delicate Stonewort Chara virgata

Plant evolution: Bryophytes

Bryophytes are mosses, liverworts and hornworts. I’m yet to illustrate a liverwort or a hornwort, but they can be really pretty, like green leathery cloaks across the ground. They like moist environments, and often decorate cliffs by streams and waterfalls.

Mosses are subjects that I have been asked to illustrate.

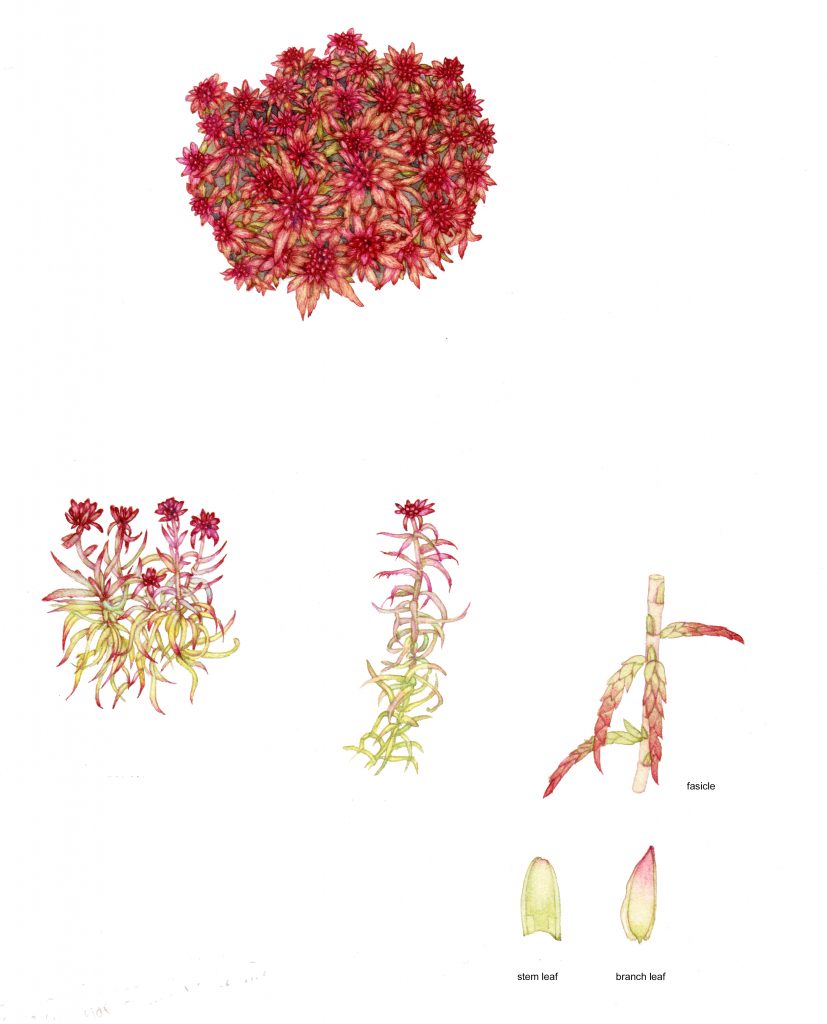

Red bog moss Sphagnum capillifolium tuft

For many millions of years, land masses on planet earth were covered in moss, without any other plants in existence. It is an almost impossible mental image. Moss reproduce with spores, and need water to reproduce. Spores appear in tiny capsules which are held above the blanket of moss below. Bryophytes are haplodiploid, which means there’s an alternation of haploid and diploid generations, and like all the other early plants they have neither flowers nor seeds.

Common haircap moss Polytrichum commune

Plant evolution: Lycopods

Lycopods come to dominate after the mosses and liverworts. They have vascular tissue so could grow high, into enormous tree-like structures.

The Club mosses we see today are far smaller, and can grow horizontally. You might see them growing on moorland or heath, especially in Scotland. For more the Stag’s horn clubmoss, one of our commonest Lycopods, click here.

Stags horn clubmoss Lycopodium clavatum

Plant evolution: Ferns & Angiopteris (Tree ferns)

Ferns are still much in evidence today, again, favouring moist habitats where their spores can fertilize aquatically, often in a thin film of water. There’s an abundance of variety in the form of ferns, some having divided and sub-divided leaves, others with smooth complete fronds.

Harts tongue fern Asplenium scolopendrium

Tree ferns can grow to massive heights to this day, in the right undisturbed habitats. There are enormous ones in the rain forests of Kalinga, Philippines.

Illustrating Bracken Pteridium aquilinum

Plant evolution: Horsetails

Horsetails are often referred to as “living fossils”, and they are indeed truly ancient.

They produce spores from a cone or strobilus. Most prefer moist environments, and in the UK they rarely grown higher than about 1m tall. In Mexico, some species reach over 8m!

Horsetails have a distinctive appearance, with bristles or leaves coming off a central ridged stem. For more on horsetails click here.

Water horsetail Equisetum fluviatile

Plant evolution: Gymnosperms

Gymnosperms are the first plants to bear seeds. This enabled a massive explosion in the places these colonising plants could grow.

They’re pollinated by wind, and seeds are borne in cones. The seeds themselves are referred to as “naked” as they’re not enclosed in a fruit. However, animals have evolved to exploit this rich food source – just consider the Red squirrel or the Crossbill.

Dwarf Pine subspecies cones

Conifers, Cycads, and the Ginko tree (yet another plant always called a “living fossil”) are all Gymnosperms.

Gingko Ginko biloba

Of course, the most enormous plants on earth are Gymnosperms; the Giant Redwood tree. These heights owe everything to the earlier evolution of vascular tissue which put ferns, horsetails and eventually Gymnosperms head and shoulders above the competition.

Giant Redwood Sequoia sempevirnes

Plant evolution: Flowering Plants (Angiosperms)

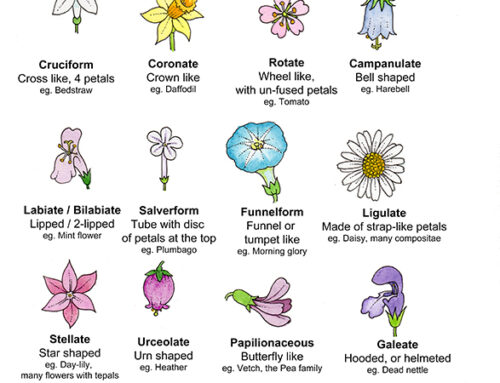

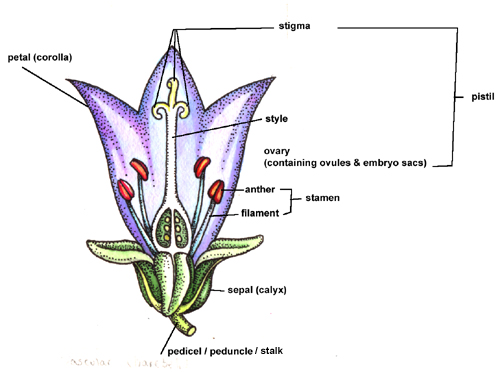

Modern seed bearing plants are incredibly successful, clothing and dispersing their seeds in an astonishing variety of ways. Many advertise their pollen to insects, birds and mammals with complex and glorious flowering structures. Others rely on the wind. There’s not enough room to even begin a comprehensive overview here, but I’ll touch on the four main groups of flowering plants.

Overview of a Eudicot flower

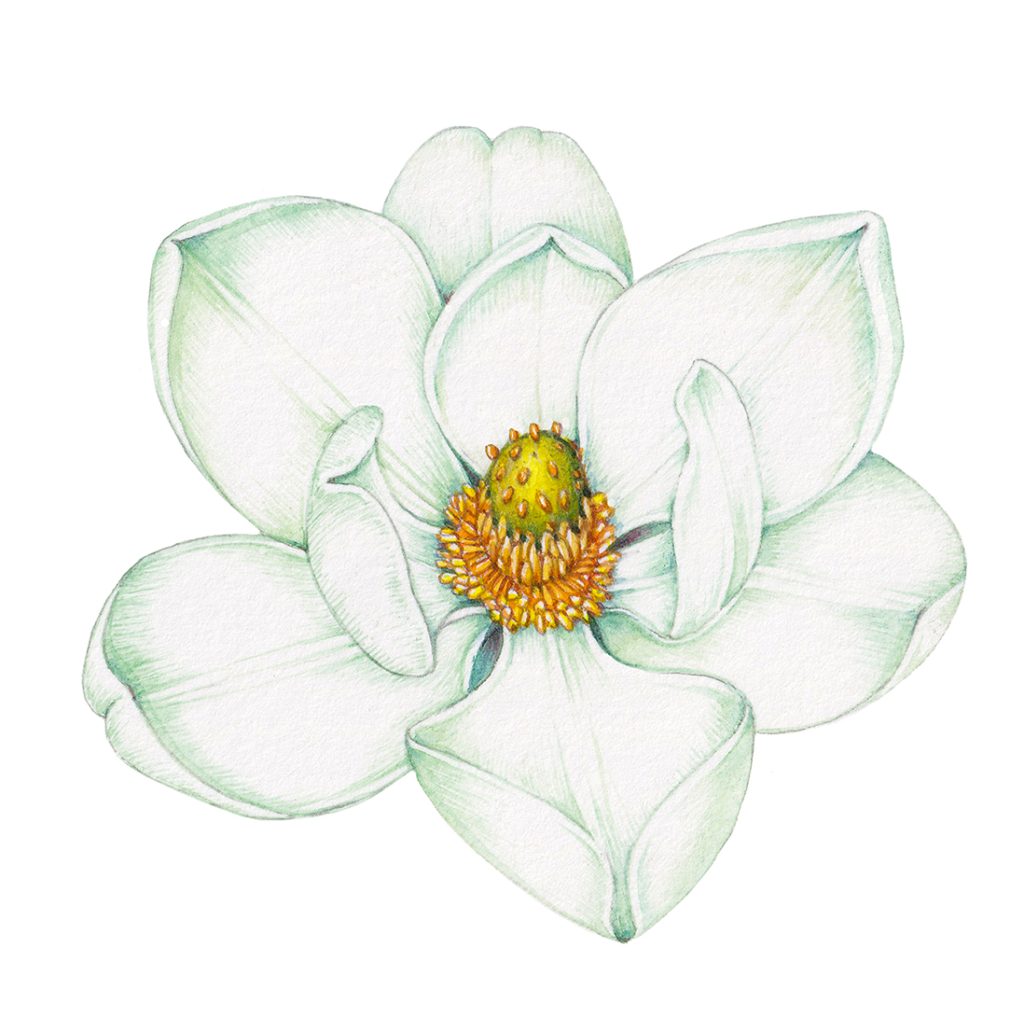

Plant evolution: Flowering Plants: Magnolias

Magnolia are considered one of the oldest flowering plants. They’re truly ancient, dating back 95 million years. Although they have petals and sepals, these aren’t clearly distinguished from each other. They are pollinated by little beetles.

Magnolia grandiflora

One of the many magnificent facts about the Magnolia is the longevity of its’ seeds. Remember how we referred to a seed as a “box with a plant inside”? Well, magnolia seeds which fell from the tree thousands and thousands of years ago can be planted up, and will grow to a successful adult tree. This blows my tiny mind.

Magnolia

Plant evolution: Flowering Plants: Paleoherbs

Paleoherbs are also known as Basal angiosperms and, like Magnolia, are very ancient. This whole group was entirely new to me, and exists as many of the plants referred to as Paleoherbs share features of the eudicots and of the monocots. Plants in this group include the Aristolochiales (Dutchman’s pipe), Piperales (Black Pepper, Wild ginger), and Nymphaeales (lotus and Waterlilies) For more on Paleoherbs, have a look at the introduction from Berkeley College, California.

White waterlily Nymphaea alba

Plant evolution: Flowering Plants: Monocots

And so we arrive, finally, at the true flowering plants. These are divided into two main groups, the monocots and the eudicots.

Monocots tend to have parallel leaf veins, leaves often grow from the base of the plant, flowers are three-partite. They grow from grains or bulbs.

Spring squill Scilla verna

Orchids, flowering blubs like tulip, Arums, iris, and my favourites the grasses, sedges and rushes are all monocots. It’s worth remembering most of our food crops (rice, maize, wheat, barley, rye, oats) are also monocots.

Grasses: Cocksfoot Dactylis glomerata, Deschampsia, Agrostis

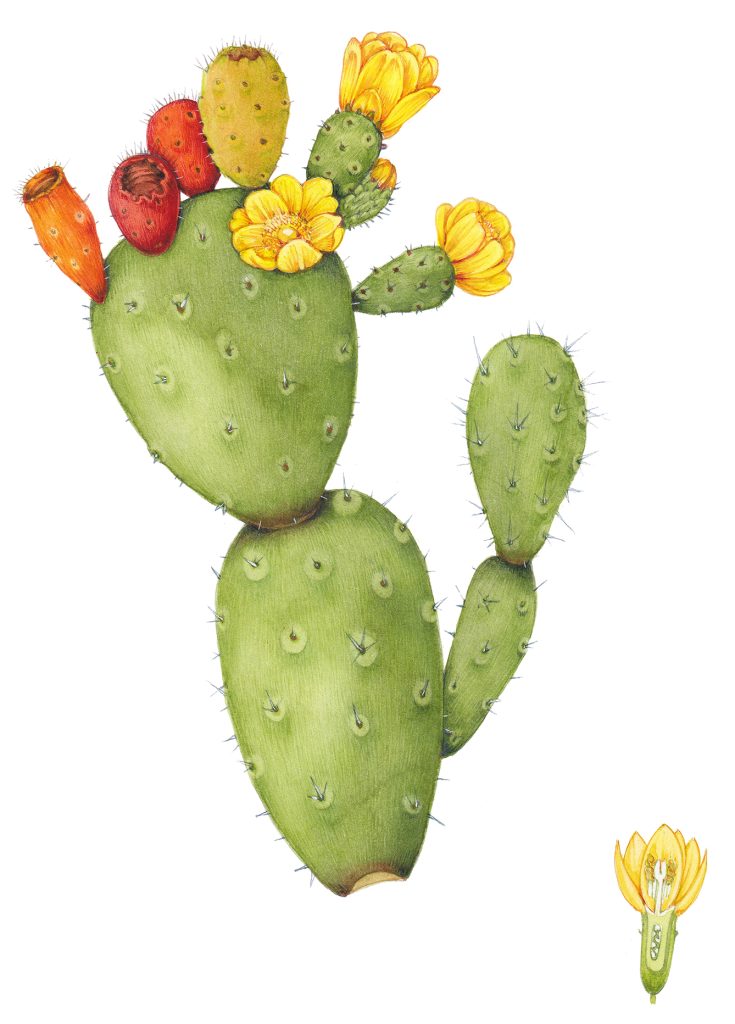

Plant evolution: Flowering Plants: Eudicots

Eudicots mostly have leaves with a branching or netted vein pattern. Their flowers have parts (eg, stamens, petals) in multiples of 4, 5, or 7. Plants grow from a seed with two sides (think of a bean seed).

Some Eudictot families have heads with lots of flowers held together, in an inflorescence; not just one flower on the end of a stalk. This is true of the Asteraceae, the daisy family. Each of the outside “petals” is a ray floret, each tiny spot in the centre is a mini flower. Take a look with a hand lens, it’s amazing.

African daisy Gerbera

75% of flowering plants are Eudicots, and they cover plants as diverse as the Cactus to the Lime tree, the Creeping thistle to the Potato, the Pomegranate tree to the daisy.

Prickly pear Opuntia ficus-indica

For more on the differences between Monocots and Eudicots, please check out my blog.

It’s the combination of that strong, safe seed; and co-opting animals or the wind to help pollination that’s led to this dominance. Flowers are a by product that we get to enjoy, and to illustrate. Fruit and nuts work for seed distribution, and feed us. With these adaptations there are hardly any habitats on earth that the Eudicots can’t exploit. They are indeed dominant.

Common Blue-sow thistle Cicerbita macrophylla

Conclusion

But I’m more in awe of the amazing variety and persistence of the plants that live on this planet.

From the unicellular green algae, still living in ponds and puddles as they did 400 million years ago. To the Charophytes, unchanged and still growing in waterways. The mosses which once blanketed the world and which still swaddle vast tracts of tundra and moorland. Ferns, in all their beauty and variety remain massively successful – just look at Bracken on UK hillsides. The strangely beautiful Lycopds and Horsetails. Conifers and cycads, shedding cones as they have done for millenia. Magnolia, enticing beetles with pollen all those millions of years ago.

Sphagnum magellicum

Please don’t disregard these plants, simply because they’ve not put their energies into growing pretty flowers to entice pollinators. Instead, be awed by the majesty and history of the entire varied kingdom. And perhaps we should all feel a little humbled by these temporal giants, too.

Enormous thanks are due to Chris Thorogood and to Julia Trickey – without Julia’s amazing series of talks I’d have never got to learn any of this fascinating information. And without Chris and his extraordinary knowledge and ability to engage and enthuse, I wouldn’t have even known where to begin.

Euglena, a unicellular aquatic green algae

The post Plant Evolution: A brief overview appeared first on Lizzie Harper.