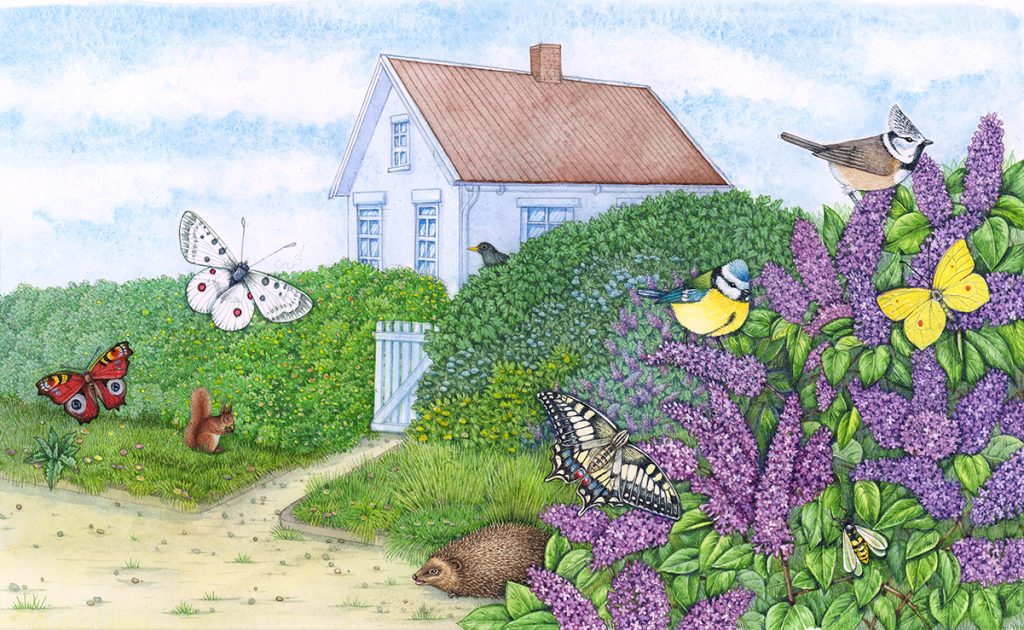

Illustrating a wildlife garden is always a challenge, but something I embrace. Not only is it an opportunity to show, visually, good practice; it also gives me the chance to learn new hints and tips on how to make my own garden more friendly to wildlife.

The twist on this commission is that this good garden needs to be cited in Sweden, which means a whole lot of research into Swedish hedging species, houses, garden plants, and native species of bird and butterfly. However, many of the over arching themes and hints on how you can improve the health of your garden, and encourage wild animals and plants, are universal.

Hedges and Edges

Gardens which are welcoming to wildlife and encourage nature tend to have hedges rather than fencing. There should be plenty of undergrowth to hide in, and hedging species should be native, or designed to appeal to pollinators. In the main illustration of the Swedish garden, Maple and Hazel make up the majority of the hedging (although from a distance it’s hard to tell what the species is!)

Hedging – Lilac is often used for hedging in Sweden

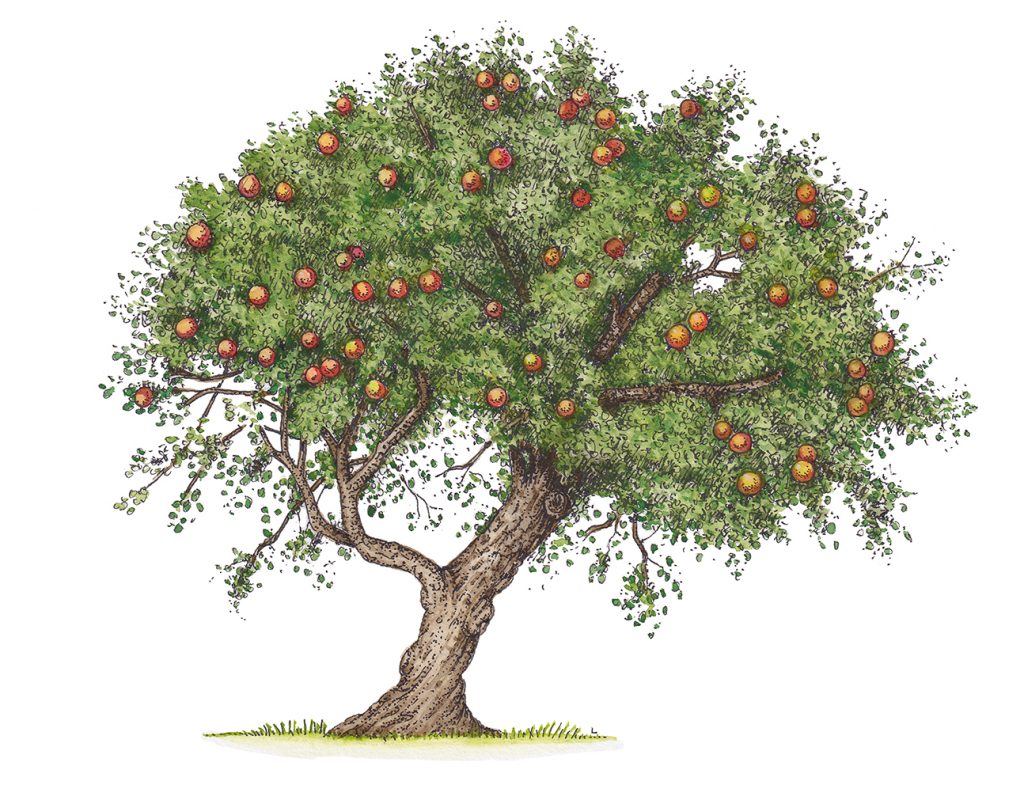

Trees and Shrubs

Old established trees and numerous shrubs and bushes are good practice in a wildlife garden. Rather than felling an ancient tree, make a feature of it. This illustration has a central apple tree, with an area of young Birch saplings on the right. Fruit trees are excellent in wildlife gardens as they provide blossom in the spring, and fruit in the autumn. These benefit both the gardener, and the insects, mammals, and birds you’re looking to attract. If you’re lucky, there will be other mature trees nearby. These will link to the canopy of trees in your garden, making it easy for birds and insects to access your space.

Apple tree Malus domestica

Shrubs illustrated include more Hazel, and Buddleja. Earlier in the year, Lilac provides nectar and pollen for bees, and looks lovely. Not necessarily seen as a shrub, bushes of lavender can be beneficial for pollinators too.

Butterfly bush Buddleja davidii

If and when your established trees shed their branches, try to avoid clearing it all up. Fallen wood encourages a whole different community of insects and animals, and leaving it on the ground allows the nutrients to seep back into the soil.

Apple tree with fallen branch left in situ

Woodpiles

You can introduce extra rotting wood into your garden by having a wood pile. Allow this to rot a little, don’t be too keen to keep it neat and tidy. Ivy, brambles, nettles and long grass growing around it provide perfect cover for animals seeking sanctuary, or somewhere to hibernate over winter.

Logpile with Hedgehog Erinaceus europaeus

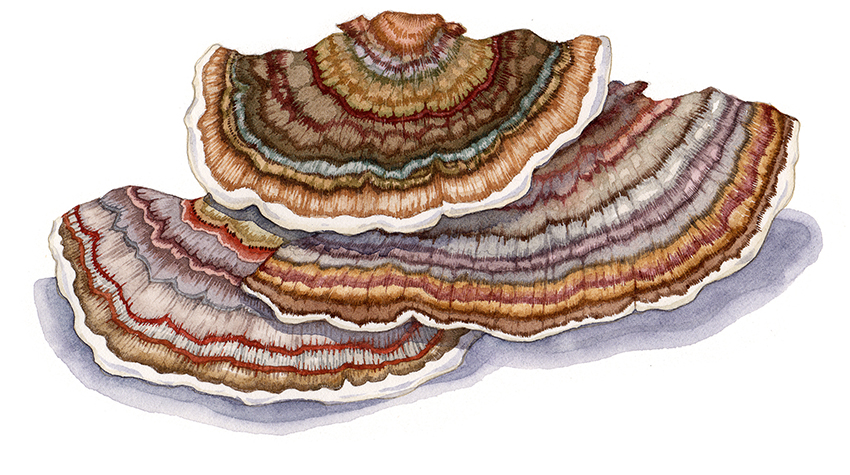

Log piles are really good for fungus too. The image above shows bracket fungus growing on the wood, along with more conventional “mushroom-like” fungi. Look out for King Alfred’s cakes Daldinia concentrica growing on fallen Ash. It looks like black balls, or burnt biscuits. Turkey tail, with its striations, also turns up in woodpiles. Fungi interact in the soil with other plants, and help recycle nutrients and encourage good soil health. They break down wood, returning carbon, nitrogen and other vital minerals to the soil.

Turkey tail fungus Trametes versicolor

The woodpile in this good garden has a Coal tit perched on top, probably looking for small insects and caterpillars to eat.

Woodpile

Minimize Hard Surfaces

Straightforward enough advice. Hard surfaces such as decking, gravel beds, and patios not only stop plants from growing on those spaces. They also add to run-off from rain water, and stop the land from working as it should, like a sponge for rainfall. Instead, water pours straight off and can clog drains and lead to flooding. More on this in this article by the British Association of Landscape Industries.

Hard surfaces can also get dirty, and people may use harsh cleaners to keep their paves areas pristine. Run-off from these can flow into water courses and damage local wildlife ecosystems.

Avoid Visible Soil

When trying to run a good garden, keep exposed soil to a minimum. Patches of sandy soil can be useful for mining bees, but in general, bare earth doesn’t help wildlife. When you’re growing food crops, inter plant between rows of vegetables. Allow plants to work as cover crops, shielding the soil from erosion, protecting it from having minerals and nutrients washed out, and adding to soil health as these rot down.

This illustration shows Cabbage and Leeks growing under a cover of French marigold Tagetes patula and chives. French marigold is a common companion plant, helping plants like tomato and aubergine to thrive. Although it actual competes with Cabbage, it does have the benefit of repelling Cabbage white butterflies and caterpillars, which is why this good garden combines the two. For more on Companion planting, see 10 suggestions of good companions on the Gardener’s World site.

Vegetable gardening

You can even choose to plant cover crops or green manures on areas of bare soil, expressly to improve the soil. Nitrogen fixing plants like White clover or Alfalfa are good for this.

White clover Trifolium repens

Grow Perennials and grass, not Annuals and Vegetables

If you can, grow grasses and perennial flowers rather than short-lived annuals and vegetable crops which. once removed, leave the soil like a desert. Some grass species are highly ornamental and look beautiful. Many wild flowers are perennial, such as Cornflower and Foxglove. Obviously, these will vary according to where you’re gardening. Perennials are good for the gardener, too. You no longer need to go and buy new bedding plants every year. Perennials will return year after year, and many will also self seed.

Foxglove Digitalis purpurea

Planting grasses and perennials, be they native or not, is a good way to look after both animal visitors and the soil. For more on what to plant, and how best to encourage butterflies to yoru garden, check out my blog.

Compost

Every good garden will have a compost heap, or two. Worm bins are excellent ways of getting the most from food waste, you can even build your own! Making your own compost means you don’t need to spend money on fertilizer or, even worse, buy unsustainable peat.

Compost heap

For information on how to make your own compost (and it isn’t difficult) check out this guide from the Wildlife Trusts. Compost rots down, so it’s a good way to get rid of garden waste without resorting to bonfires or taking green waste to the tip.

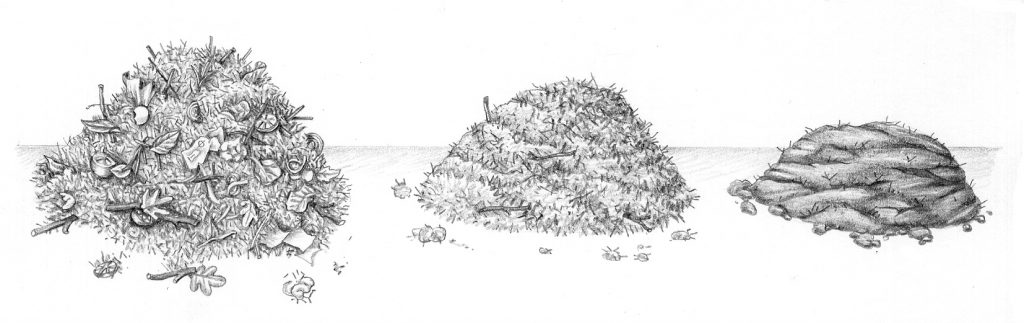

Compost degrading over time

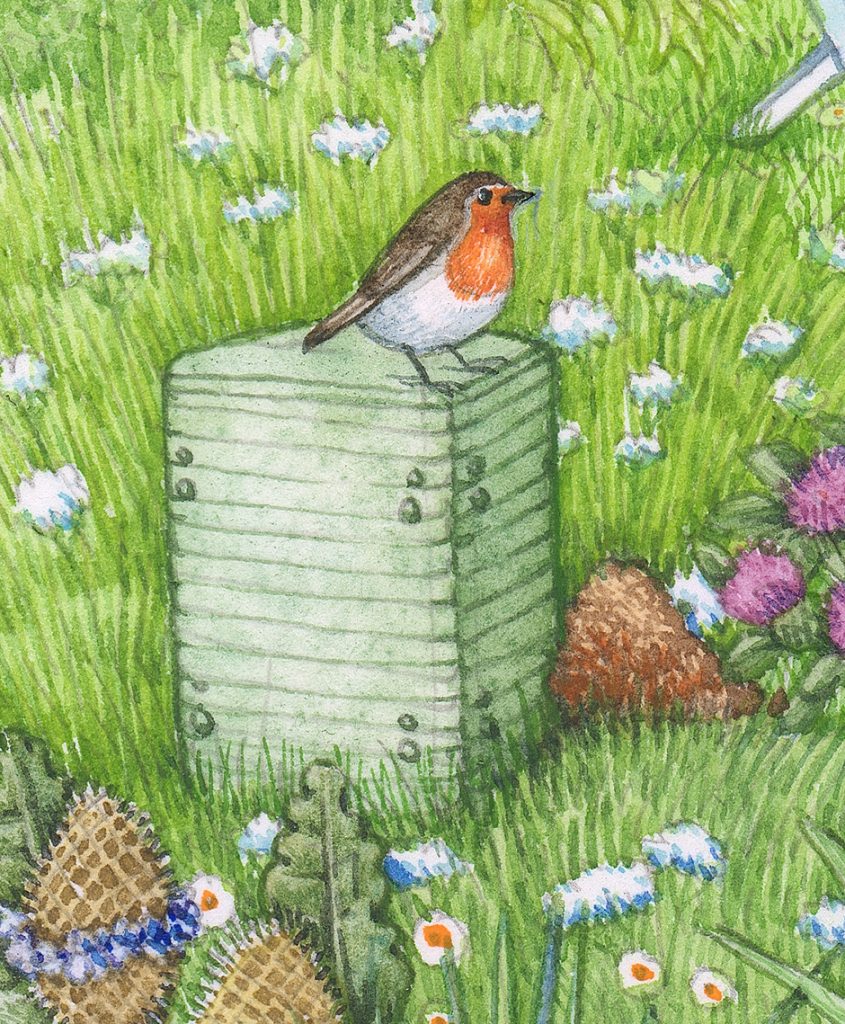

In Scandinavia (as elsewhere), thermal composters are popular. This method of composting basically compresses compost, meaning the layers of organic matter and microbes involved in decomposition are in closer contact. Garden waste may need to be broken down into smaller parts with a chipper, but the benefits are higher yields of compost and compost free of weed seeds. It also doesn’t smell, is ready in 30 – 90 days, breaks down pesticides, and kills eggs and maggots of flies.

Hot composter with Robin perched on top

Leave Weeds on the Flower bed

This is new to me, but leaving weeds on the flower bed keeps the soil covered, and allows their nutrients to leach back into the soil.

Weeds left to rot on soil

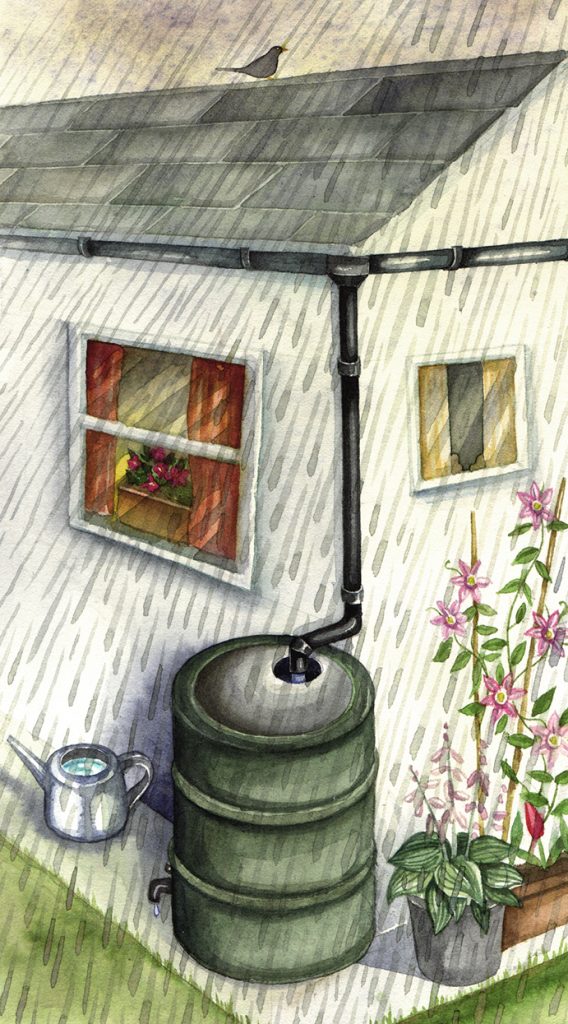

Rainwater

Preserving rainwater is a great idea if you’re wanting to create a good garden.

Water but on left hand side

Water butts can be fixed to guttering, and will collect all the rain water that falls on the entire roof area. Rain water is free from chemicals which are added to water that we get from taps; things like chlorine and fluoride. Tap water isn’t bad for watering plants, but rainwater is much better. According to the Royal Horticultural Society, rainwater “is free from hard water elements and is the correct pH for the majority of plants, including acid-lovers such as rhododendrons and camellias.”

Water butt collecting rain from the roof

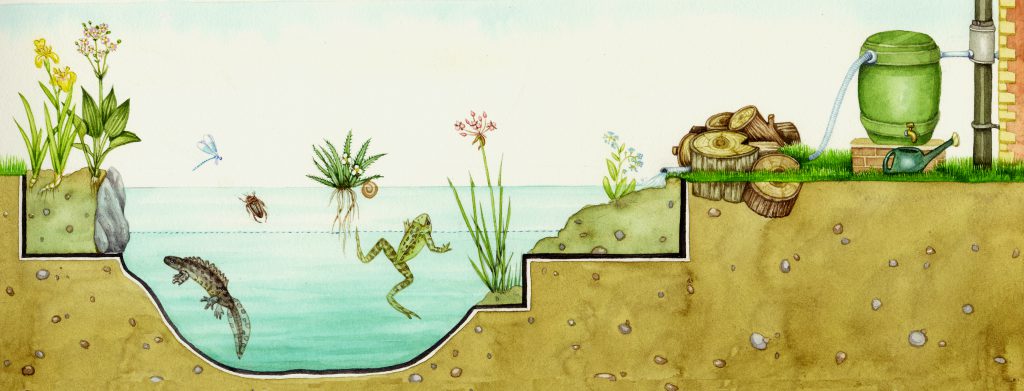

Although it can be tricky finding enough places to put water butts, looking after rain water is a really good idea. You can also combine it with installing a wildlife pond.

Wildlife pond being fed by rainwater

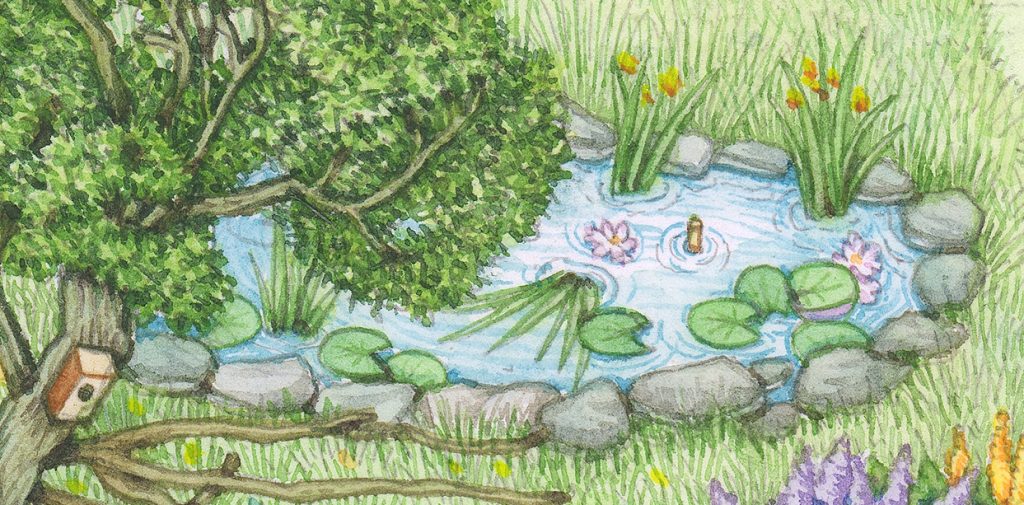

This is another excellent idea which encourages wildlife. Rain water, devoid of chlorine, is by far the best option for aquatic species. For more on how to establish a wildlife pond, check out the Wildlife Trust’s guide.

Wildlife pond

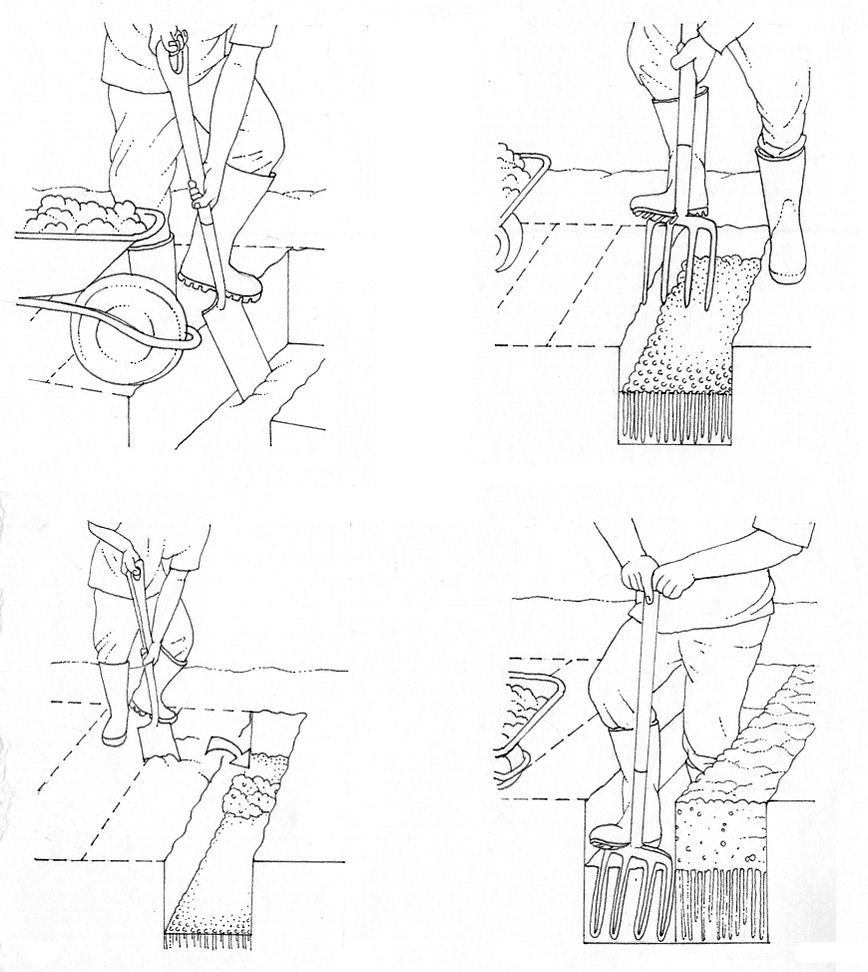

No dig Garden

Digging used to be de-rigeur for any gardener. Many would double dig, every year. Recent research suggests that doing this can be really bad for soil health. It breaks up the microscopic networks of fungal hyphae, stopping them from interacting with the roots of plants. There’s a lot of symbiosis between fungal and plant roots, on a cellular level, and such brutal treatment of soil makes this relationship impossible to sustain.

Double digging is now thought to be bad for soil health

But how can you aerate the soil, making it light enough for plants to grow into? In the past, this was seen as one of the prime reasons for digging.

Alternatives are numerous. You can plant Teasels Dipsacus fullonum, or other plants with seriously long and strong tap roots which break up the soil. Teasels are also great for wildlife as their seed-heads produce thistle-like seed deep into winter, a real treat for goldfinch and other birds.

Goldfinch Carduelis carduelis and teasels

Mulching, growing a green manure like clover or alfalfa, and adding organic matter all help break up the soil. Without damaging that all important fungal – plant symbiosis. The Welsh Botanic Garden have more on the benefits of a “no dig” system.

Introduce Climbing plants

The more surface area you can cover with green growth, the better. Good gardens not only grow horizontally, but vertically too. This means putting up trellis on buildings, and encouraging climbing plants. Roses or clematis clambering up a house can look wonderful, and provide wonderful safe havens for overwintering insects and nesting birds.

House festooned with climbing plants like clematis, wisteria, and rose

Sometimes, you don’t even need to do any planting. In my garden, Ivy sprawls across the whole of the back wall. In winter it’s alive with flies and hoverflies, and spring sees it full of sparrow nests. Although it’s not great for the wall, on balance I think it’s worth it. And I never lifted a finger!

Ivy Hedera helix growing on a wall

Some plants are remarkably good at growing up things. Old Man’s beard, Clematis vitalba can swallow up an abandoned building or a dead tree, and provide lots of safe spaces for wildlife. Although this is an introduced species in Sweden, it’s become so ubiquitious that many Swedes are surprised to hear that it’s not a native plant.

Old Man’s Beard Clematis vitalba

Don’t Mow too much!

Mowing a lawn too often is a sure fire way to turn a good garden into a wildlife desert. Even if you like carefully manicured turf, consider leaving islands of long grass unmown. Small mammals can live in these pockets, and the long grasses shelter insects like grasshoppers, ants, and beetles.

Short tail or Field vole Microtus agrestis in grass

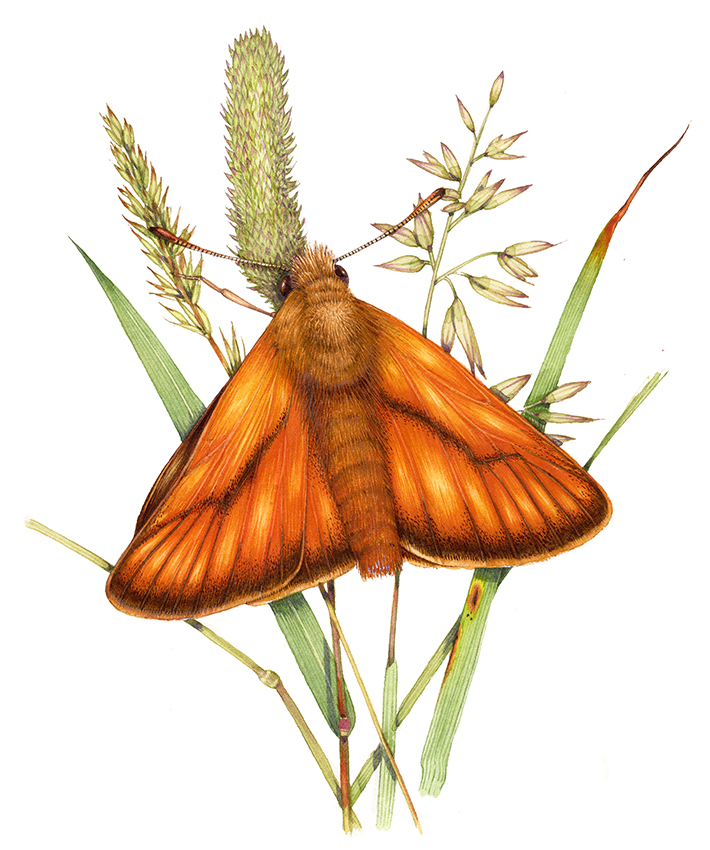

Pollinators thrive, feeding on the nectar and pollen of the wild flowers that inevitably also grow in these long-grass islands. Many caterpillars have grasses as their main food plant. It’s thought that you can bring up to 10x more bees to your garden if you simply avoid mowing all your grass too much (Plantlife 2019)!

Small skipper Thymelicus sylvestris on grasses

In the UK there’s an initiative called “No Mow May” in which gardeners and local councils are encouraged to put aside the lawn mowers for the month of May and allow butterflies, pollinators, and wild flowers to thrive. It’s been hugely successful, and is becoming a given for any good garden.

Long areas of grass left unmown

Conclusion

There are many things you can do to turn your outdoor space into a good garden. Don’t feel guilty if you’re unable (or unwilling) to make all these changes, or make them all at once. Every small step taken will help. And whether you’re gardening in Sweden, Britain, America, or anywhere else; trying to do something to help encourage wildlife and wild flowers in your own backyard has got to be a good idea.

For lots of good resources on how to garden well for wildlife (in the UK), check out Plantlife’s website.

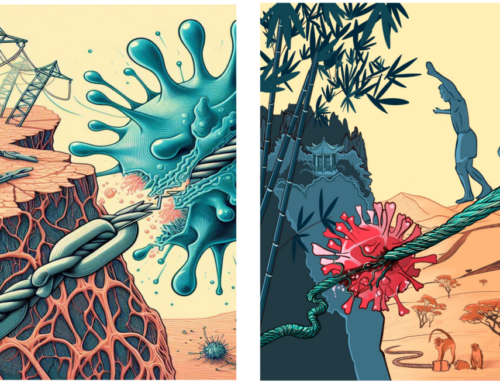

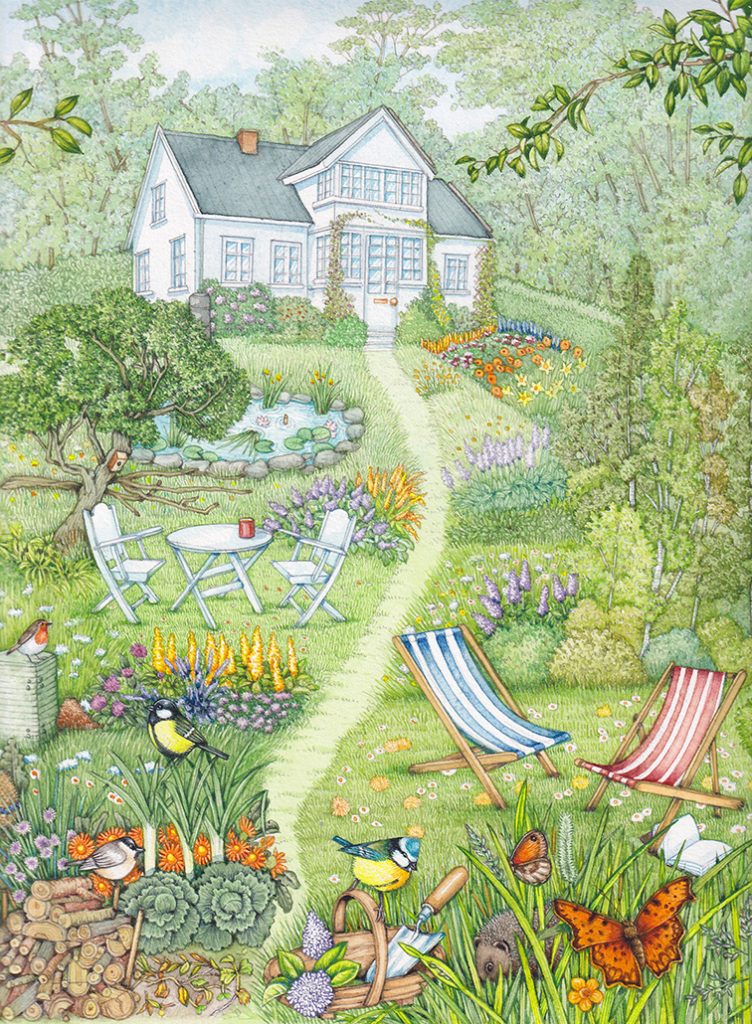

Completed illustration of the “good garden”

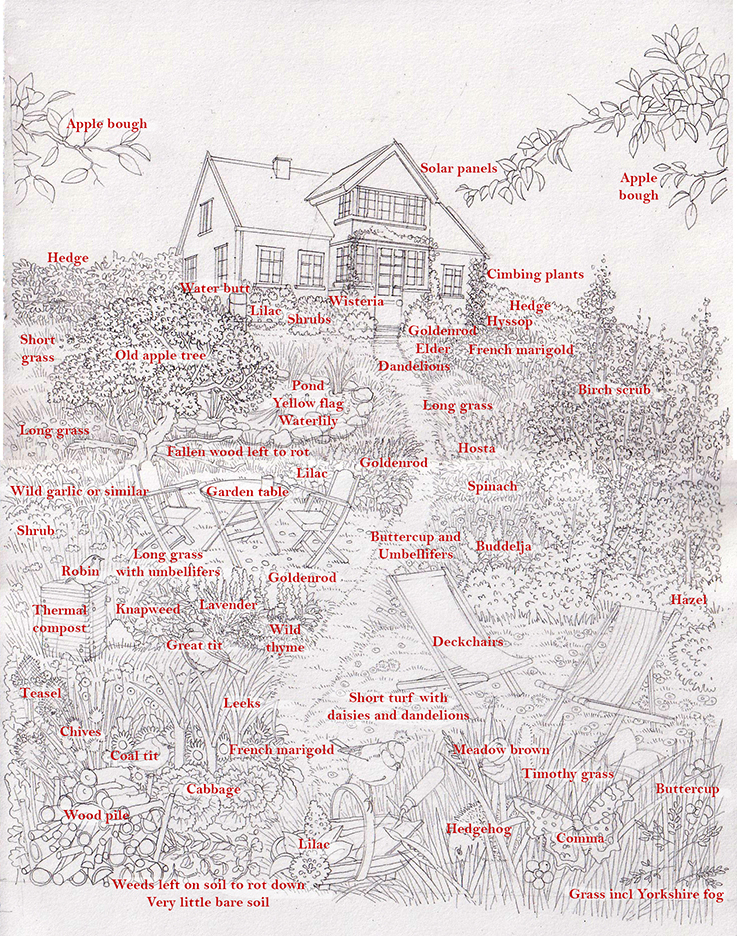

Below is the annotated pencil rough of the Swedish “good garden” illustration. It might help clarify any parts of the finished illustration that seem unclear.

Annotated wildlife garden illustration

The post Good Garden: A wildlife Haven appeared first on Lizzie Harper.