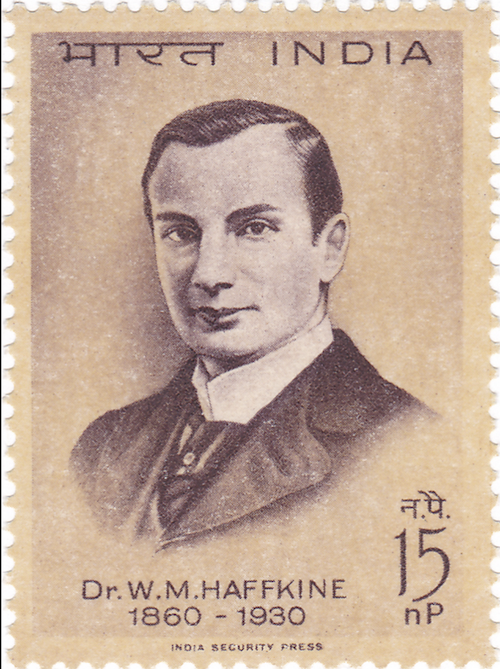

On January 10, 1897, a plague vaccine was first administered to a person. The creator of this vaccine, microbiologist Vladimir Khavkin, injected himself. Louis Pasteur’s prediction began to come true: “One of my students will stop the plague.”

Pasteur said this, already dying, the last time he arrived at his institute. During this visit, he was shown the causative agent of the plague under a microscope – a bacterium just discovered by his student Alexandre Yersin.

The third pandemic of the plague began: a terrible disease escaped a natural focus in central Asia and attacked China, Russia, and India. Pasteur’s lowest-ranked student, a citizen of Russian Empire Vladimir Aaronovich Khavkin, just returned from India. However, he was no longer even a Russian by the papers. Khavkin missed visiting the Russian embassy in time to renew his passport.

In Russia, Vladimir was considered politically unreliable as a member of extremist organization Narodnaya Volya. He was arrested three times and 8 years under the supervision of the police. Without much regret, the Russian ambassador issued a letter of recommendation to the British government, which invited Khavkin to India to test his cholera vaccine, another of Vladimir’s inventions.

Both Khavkin’s sponsor, Ilya Mechnikov, and Louis Pasteur himself doubted the efficiency of this vaccine. However, the result was excellent – 93% of guaranteed protection. Believing Khavkin to be a wizard, the British called him again – now to fight the plague. They accepted a full-time biologist into the civil service, promised British citizenship, and a laboratory.

The laboratory at Bombay College of Medicine was assigned with unprecedented generosity – a whole room. Lab staff consisted of one assistant and three couriers. The experimental animals were rats provided by sailors from ships coming from Europe. Simultaneously with Khavkin, several other research centers developed the plague vaccine in much more luxurious conditions. And yet, a passportless immigrant outstripped everyone.

He chose the path that others did not follow: to make the toxin produced by the plague microbes. Bacilli were bred in meat broth. To provide bacteria with something to catch on, Khavkin dropped a drip of fat into the liquid. Microbes clutched at a greasy spot and grew down like stalactite. These “Khavkin stalactites” testified that bacteria felt great. From time to time, the flasks were shaken, the bacilli dispersed, another drop of fat was placed onto the surface, new microbes clung to it until the broth was saturated with the toxin.

Before injecting this poison into rats so that they develop immunity to the plague, the flasks were heated to 60 degrees – such pasteurization killed the bacteria, preserving their toxin intact.

A test batch was prepared in just three months. The laboratory assistant had a nervous breakdown, and Khavkin worked 14 hours a day: he was in a hurry, hundreds of people died around daily. At the same time, he also read lectures to local medical students about the future vaccine. Apart from them, no one would dare to get vaccinated even after the Russian microbiologist on January 10, 1897, drove the fourth dose of plague poison under his skin – 10 milliliters of toxin solution.

Nevertheless, it was easier for Indian students to agree to vaccination because Khavkin came from Russia. The measures with which the British colonialists fought the plague aroused a lot of animosity among the natives. The commander of the Bombay garrison, General William Forbes Gatacre, acted with little care or wisdom, and no one had a say in his dealings. The military rounded up plagued patients to hospitals and their families to camps. Thus, direct contacts between healthy people and infected who were still undergoing the incubation period were established. The empty houses of the unfortunate captives were flooded with carbolic, and rats ridden with plague fleas scattered everywhere, spreading the infection.

The Mandvi region, which was populated by the poorest, suffered the most. But they did not want to be vaccinated. In vain, did Indian students repeat to them that the vaccine was made locally, and its creator was not “Angrez”, but “Rusi.” And this “Rusi” is just as persecuted because he is a Jew, and openly says that the British are as ill-disposed towards the Indians as the tsarist authorities are to their people. For the poor from the slums of Mandvi, all the whites were on the same page.

Only an influential person whom they trusted could convince them to get vaccinated. And such a leader was found. He addressed Khavkin personally.

It was Sultan Mahomed Shah, Aga Khan III, the ruler of the invisible Ismaili empire, the 48th imam of the Nizari Ismaili sect, guiding this Muslim community in anticipation of the appearance of the Messiah Mahdi. Barely 20 years old then, this young man knew 5 languages and was well-versed in the sciences, so that he could evaluate the possibilities of the vaccine by the articles in the medical periodicals.

He had just married, and his subjects, scattered from Mozambique to Indonesia, presented him with gold coins, the total weight of which was equal to the weight of the 48th Imam himself. There was enough gold, but the British methods of combating the plague alerted him.

Aga Khan hatched far-reaching political plans. For a career boost, he needed a heroic feat., which he got it. At the request of the omnipotent Imam, Khavkin several times vaccinated him in front of crowds of Ismailis. Vladimir’s laboratory moved from a cramped room to Aga Khan’s luxurious villa, and the staff doubled. It worked.

Eleven thousand Ismailis were vaccinated immediately. Now, both the disease and the damned British plague fighters eluded their lodgings. Seeing that Aga Khan was “for the people,” the Ismaili neighbors began to convert to Islam, joining the ranks of the Shia sect. Here the leaders of the Hindus sensed competition and began to persuade their fellow believers to also vaccinate. Additionally, they announced Khavkin mahatma – a saint.

Aga Khan got everything he wanted from this scientific experiment. Queen Victoria showered him with awards and gave him a place in the Indian government. In West India, populated mainly by Muslims, the elites of future independent Pakistan grew from the protegees of Aga Khan. When this state gained sovereignty, Aga Khan again was weighed. But now, not gold, but diamonds were strewed onto the other side of the scale—95 kilograms of diamonds.

On a side note, Khavkin realized who he was dealing with right away, back in 1897. He had his interest in Aga Khan. In turn, Vladimir proposed to the Imam a project for the liberation of Jews from the rule of other nations. According to his plan, the Ottoman sultan Abdul-Hamid II – Palestine belonged to the Ottoman Empire then – was to allow Jews to buy land around Jerusalem. A compact Jewish autonomy would have formed, which out of gratitude would have become the pillar of the power of the Sultan in the troubled Arab East.

Curiously, the Ismaili leader did discuss this plan with Abdul-Hamid, and the latter flatly refused.

Aga Khan III lived for another 60 years and often repeated that among all the mistakes of the last Ottoman Empire’s lord, this one was the most significant.

Source https://shorturl.at/ksLO9

Download Free eBook “How much does Medical Animation explainer cost?”

- Should you choose Freelancer or Studio as a medical animation provider?

- What is the COST structure?

- Prepare BETTER for the project

- How to SAVE the budget?

- How to AVOID common mistakes?

});

The post First Plague Vaccine – Vladimir Khavkin appeared first on Nanobot Medical Animation Studio.