My recent botanical illustration work for a Field Studies Chart (as yet unpublished) on Invasive species included 5 species of Cotoneaster.

Telling these plants apart can be a real headache, but I’m going to give it a go, and share my thoughts. I’m more than happy to be corrected in the comments section below!

Cotoneasters are really common, They’re a mainstay of municipal planting and can be found in car parks, round council offices, as well as in people’s gardens. I found 4 different species in Hay on Wye town car park, very convenient! That’s nothing though, there are over 100 species which are routinely used in the UK for ornamental and landscape planting. No wonder telling them apart can be troublesome.

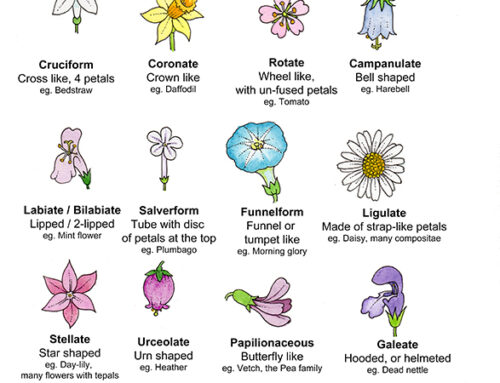

They’re low-growing shrubs with shiny leaves and distinctive red berries. They have no thorns, and the margins of the leaves are smooth and un-toothed. Leaves grow alternately. Flowers are white or pale pink, have five petals, and grow in small clusters.

These plants are invasive species because they can take over native habitats, such as limestone cliffs (Wall cotoneaster) and heathland. They can form thickets which shade out native species. Some of the displaced species are really quite rare. The seeds of Cotoneasters are viable, so may be spread by birds. Many species are becoming natuaralised across a wide range of habitats.

It should be noted that cotoneaster berries can be toxic to humans.

Below are five species of this ubiquitous plant, alongside their tell-tale species traits.

Entire-leaved Cotoneaster, C. integrifolius

Wall Cotoneaster C. horizontalis

Wall cotoneaster is probably one of the commonest species. It’s grown as hedges, and attracts swathes of pollinators when flowering. The growth habit is very distinctive, lateral branches come off a central woody stem and are more or less parallel to one another. It’s a herring-bone pattern that’s clear at any time of year.

Leaves are shiny on top and almost hairless below. They have a distinct murconate or pointed tip. The hairs which are present are sparse and large. They’re 0.6 – 1.2cm long.

Flowers are pink, have white anthers are solitary.

Berries are orange red, shiny, with a puckered 5-pointed scar. They’re borne on very short stalks.

Himalayan Cotoneaster C. simonsii

This species grows as an erect shrub, with deciduous leaves.

The leaves are oval and shiny green on top. They’re 1.5 – 3 cm long, and the underside bears a scattering of hairs. They sometimes look like they have a pale margin.

Flowers are pink and in clusters of up to four flowers. Anthers are white.

The berry is orange-red and rather oblong or ovoid. These fruits are 8-11 mm long and borne in clusters of 4 to 10 berries. They have 2-3 mm long stalks. The literature seems to be in some disagreement about whether or not the berries have hairs at the top and base of the berries. I left them off my illustration.

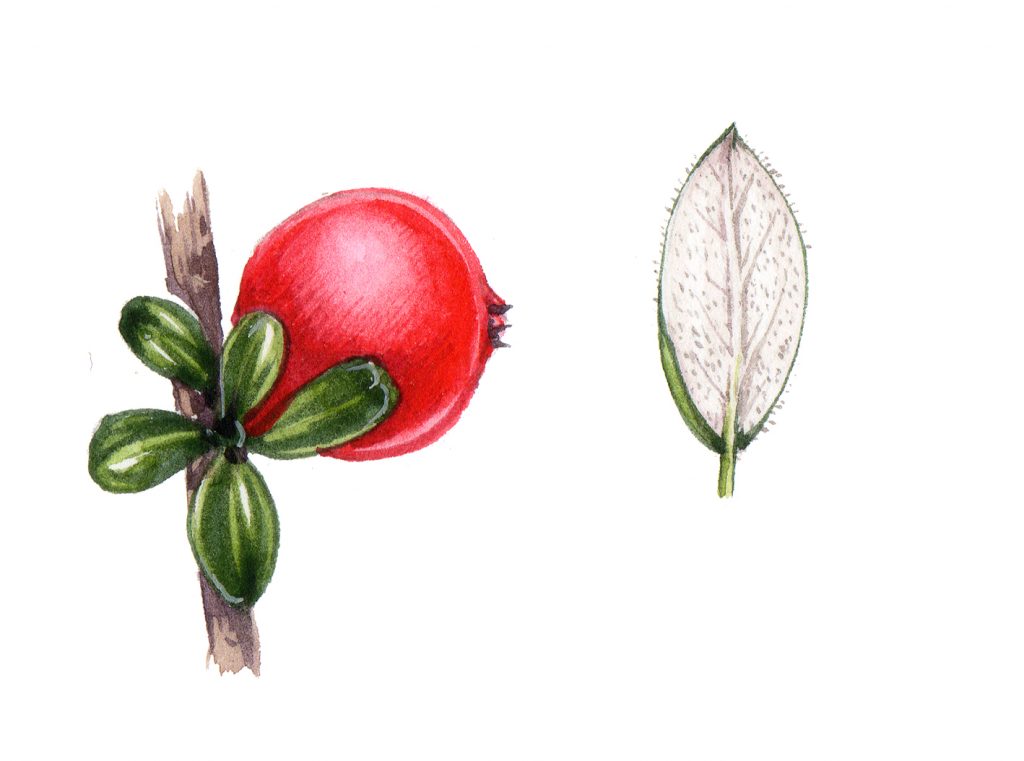

Small-leaved Cotoneaster C. microphyllus

This is another common one. It grows in low-lying evergreen shrubs, and spreads.

The leaves are glossy above, with felted hairy undersides. They’re white-grey below, and the hairs grow parallel to the surface.

Pink flowers grow in groups of us to 5. They can be told apart from other Cotoneasters because the anthers are purple or black.

Berries are scarlet or crimson and spheres of 5-9 mm. They appear singly or in pairs, on short stalks of 2 mm or less.

Hollyberry Cotoneaster C. bullatus

Hollyberry Cotoneaster is a large, deciduous shrub.

Leaves are rather different from other species. They’re larger (50 – 128 mm), and have distinctive indented and deep veins. Unlike other species, they’re a matte green on top. The underside of the leaf is paler and has hairs along the central vein.

The flowers are small, and pale pink. They may look deeper pink in bud. They’re are borne in clusters of up to 20 flowers. Anthers are white.

Berries colour readily to a vivid red, and are slightly squared. They’re bigger than in many other species, 8.5–10.5 mm. These are borne in clusters of up to 10 berries, and have a clear stalk. On close inspection, the berries are slightly hairy at the top and on the stalk.

(Info on this species comes mainly from the Flora of New Zealand site)

Entire-leaved Cotoneaster C. integrifolius

This plant grows in a markedly prostrate and spreading way, flattened in planes that can cover walls. It’s an evergreen, and you’ll see its berries and dark green leaves through the winter.

Leaves are a glossy dark green, and tend to widen above the middle. They’re often folded, and their length is greater than 2x the width. The leaves are tightly crowded along the branch, each one is 12–25 mm long. They often grow in distinctive rosettes, and have stalks of no more than 2.5mm long. The underside is hairy or wooly, and pale.; hairs are short, stiff and lie close to the leaf surface.

Flowers are white and borne singly. They have red or purplish anthers.

The berries are a give-away with this species. Not only are they very round, but they’re matte. A lovely crimson shade, with no bright shine makes them distinctive. They almost have a bloom on them. They’re 7-9 mm in size.

Can you tell that this is the species I did most work with? It was such a relief to find a species I felt certain about to illustrate!

Conclusion

I hope this rather heavy-handed comparison helps you to tell some of these species apart. Add to the confusion the fact thet Cotoneasters seem to hybridize sometimes, and it;s a real mix. Now I definitely feel confident about the herring bone Wall cotoneaster, and the matte-berried Enitre-leaved cotoneaster. So I’ll probably be sticking to those two for now!

My main source of reference for this blog is The Field Guide to Invasive Plants and Animals in Britain by Olaf Booy, Max Wade, and Helen Roy. It’s a great book, if a little depressing. The RHS also has information on different Cotoneasters, with an eye for the garden. The Flora of New Zealand website is very good on the botanical details of the different cotoneasters. However, the definitive work on Cotoneasters is the BSBI plant crib. It can be a little turgid, however, and I found it tricky to see clear differences between species in some cases (probably because I’m not a botanist).

For a few more of my blogs on telling species apart, take a look at my webpage.

The post Telling Cotoneasters apart appeared first on Lizzie Harper.