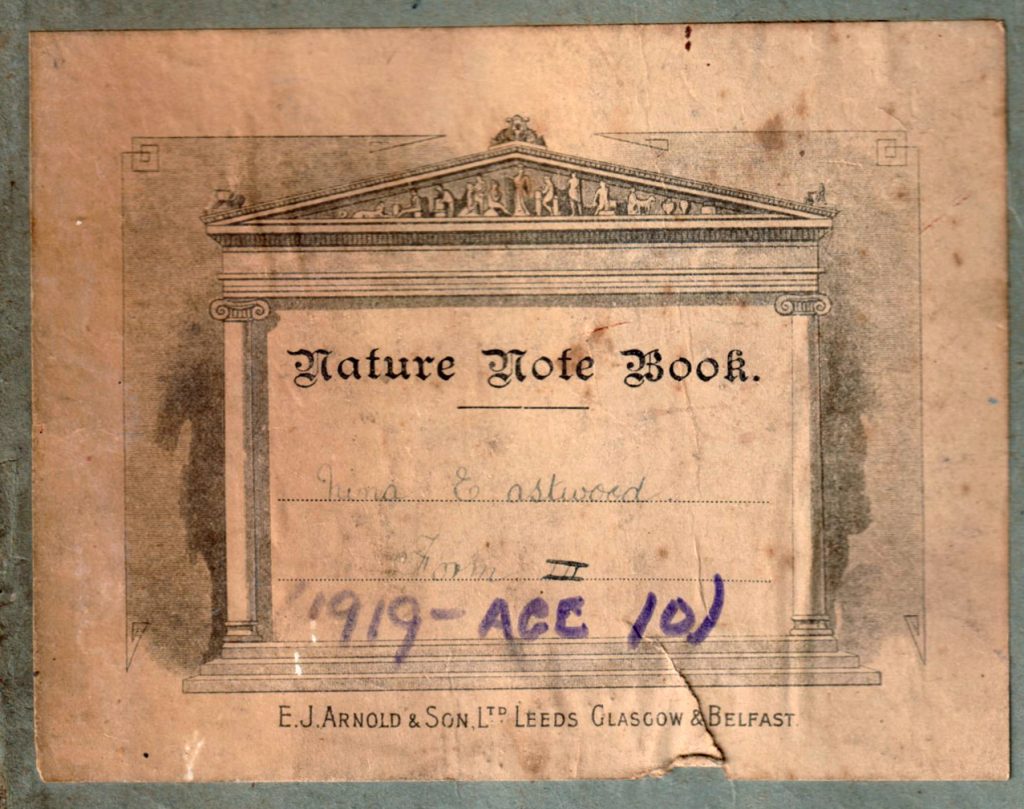

Nature notebooks seem to have run in my family for a long time. I recently found one completed by my Great aunt Nina, back in 1919, when she was ten. This got me thinking about all the other artists in my family, and I decided to share some of them, and their artwork.

Front cover of my Great Aunty Nina’s Nature Notebook

Nature Notebook: The Fly

The nature notebook is clearly a school book, but I’m amazed by the depth of knoweldege shown in the writing, and the ability Nina had to draw.

The text for her entry on the fly is as follows:

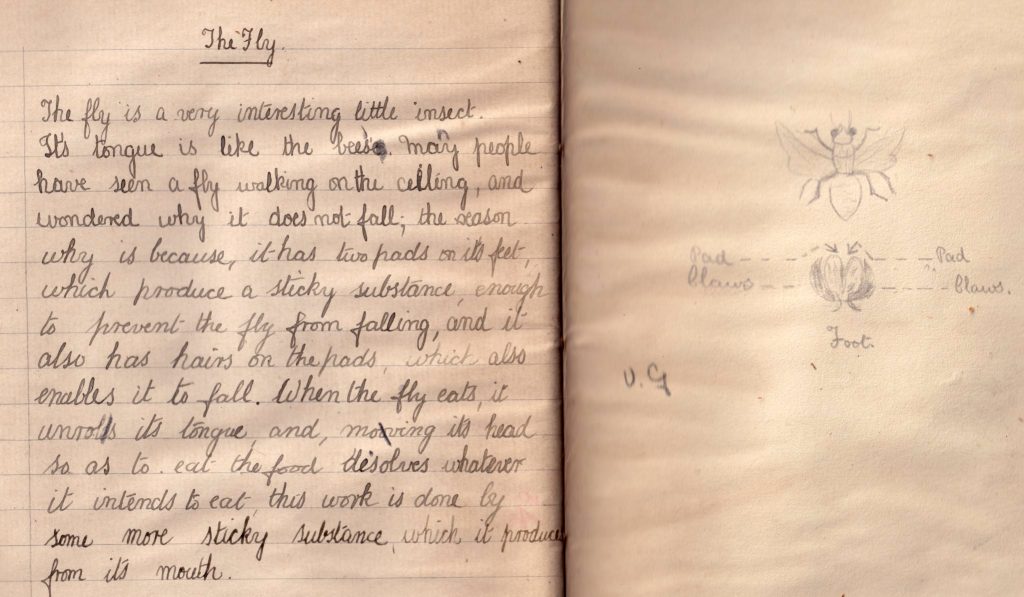

“The fly is a very interesting little insect. Its tongue is like the bees. Many people have seen a fly walking on the ceiling, and wondered why it does not fall. the reason why is because it has two pads on its feet which produce a sticky substance, enough to prevent the fly from falling, and it also has hairs on the pads, which also enables it to fall. When the fly eats, it unrolls its tongue, and moving its head so as to eat. The food dissolves whatever it intends to eat. this work is done by some more sticky substance, which it produces from its mouth.”

Aunty Nina’s entry in the Nature Notebook on the fly

Not only is this all true, but I certainly had no idea of half of this when I was 10 years old. Her illustration shows a pencil drawing of a fly, with a close up of the foot. I would love to have listened in on this lesson, and the reception it got from a room of young girls at the tail end of the Edwardian era.

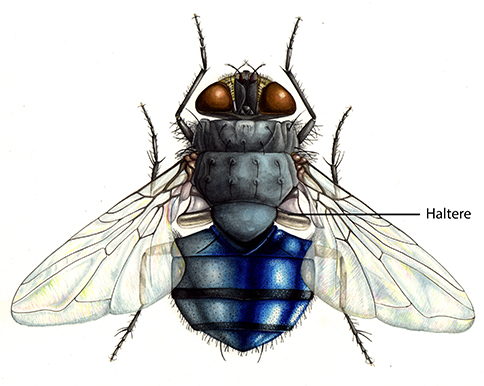

My illustration of a Bluebottle, showing the balancing “halteres”

Nature Notebook: Ants

Nina’s entry on wood ants was of especial interest to me as I illustrated a lot of wood ants earlier in the year for the Cairngorms National Park.

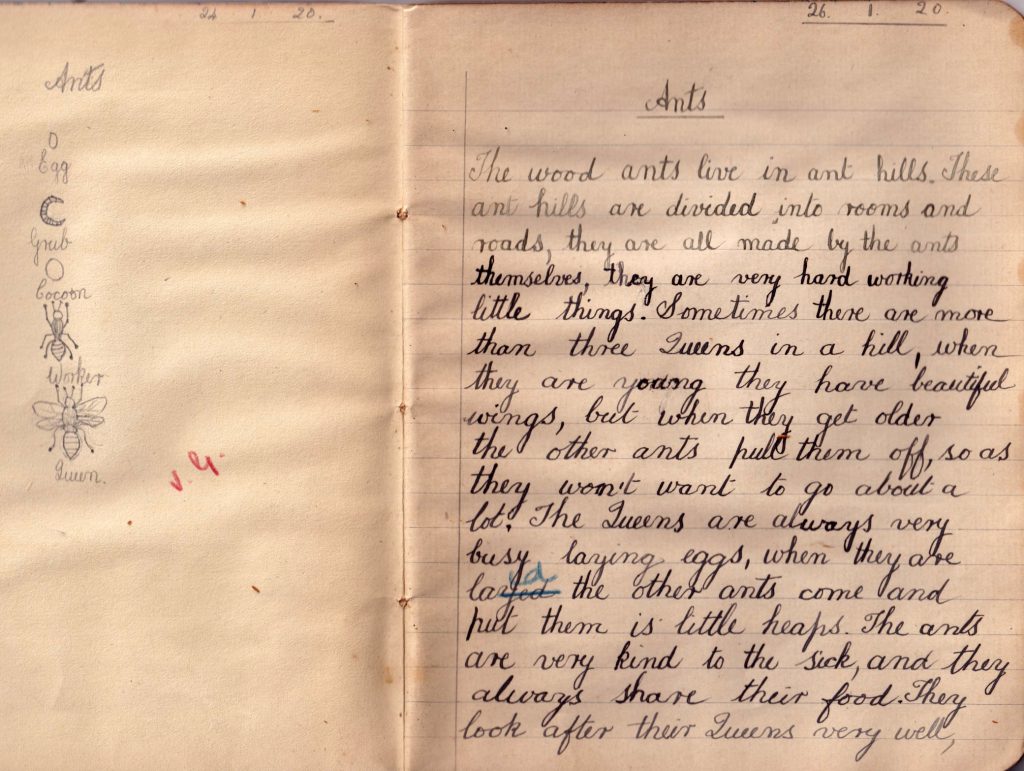

Not only has she drawn a worker and a queen ant; but has included an egg and a grub. I don’t know how these nature lessons would have been taught in 1919, I assume with large posters featuring illustrations that the girls had to copy. The idea of them having access to microscopes, let alone to ant larvae, seems unlikely. Not least because they were living in the leafy suburbs of Birmingham!

Aunty Nina’s entry in the Nature Notebook on the Ant

Her text reads, “The wood ants live in ant hills. These ant hills are divided into rooms and roads, they are all made by the ants themselves, they are very hard working little things. Sometimes there are more than three queens in a hill. When they are young they have beautiful wings, but when they get older the other ants pull them off, so as they won’t want to go about a lot. The queens are always very busy laying eggs. When they are larva, the other ants come and put them in little heaps. The ants are very kind to the sick, and they always share their food. They look after their queens very well, they never have to find their own food because the workers find it for them. Ants look after their eggs very well, they put them in the sunny part of the hill.”

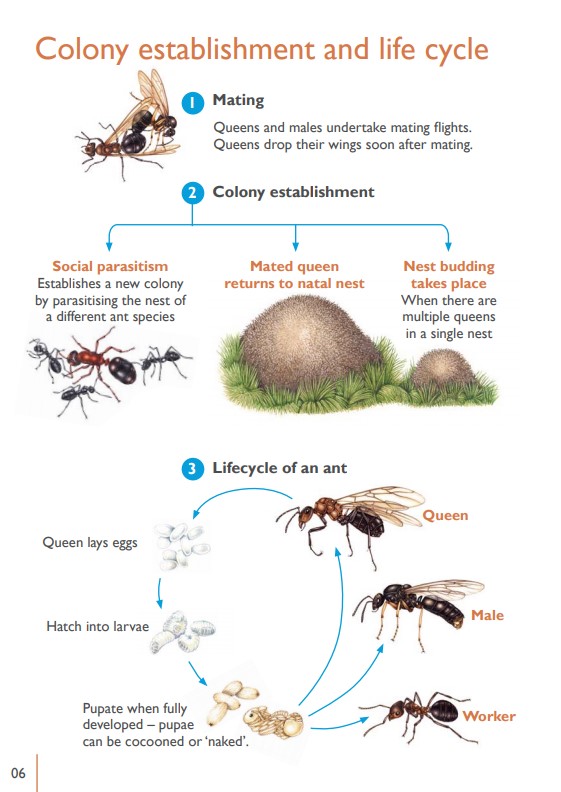

This interests me because (as far as I know!) it’s mostly factually correct. However, I think the queens bite off their own wings after mating during their nuptial flight. Perhaps things like mating were not deemed appropriate for young ladies to learn about?

My illustration of the Wood ant life cycle from the booklet published by The Cairngorms

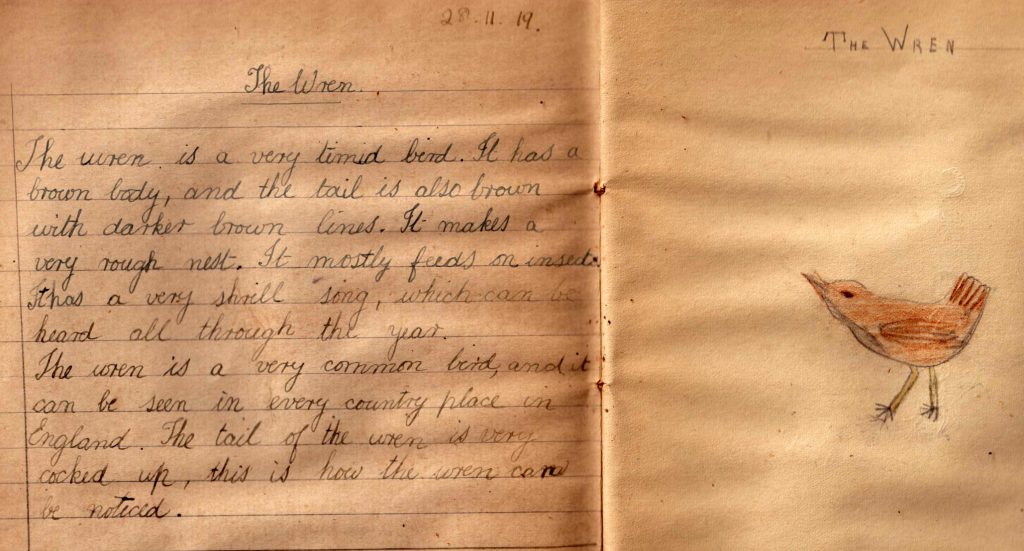

Nature Notebook: The Wren

Nina covered birds too, the Green woodpecker, Kingfisher, and Wren. In fact, her entry on the Kingfisher informed me that their nests are lined with fish scales and bones. I totally disbelieved this until I checked online. She was right, as this post from the Scottish Wildlife Trust shows. Being told a nature fact, by my long dead Great Aunt, which she learnt and wrote down over 100 years ago as a 10 year old…? I love it.

Aunty Nina’s entry in the Nature Notebook on the Wren

Her entry on the wren reads as follows: “The wren is a very timid bird. It has a brown body, and the tail is also brown with darker brown lines. it makes a very rough nest. it mostly feeds on insects. It has a very shrill song which can be heard all through the year. the wren is a very common bird, and it can be seen in every country place in England. the tail of the wren is very cocked up, this is how the wren can be noticed.”

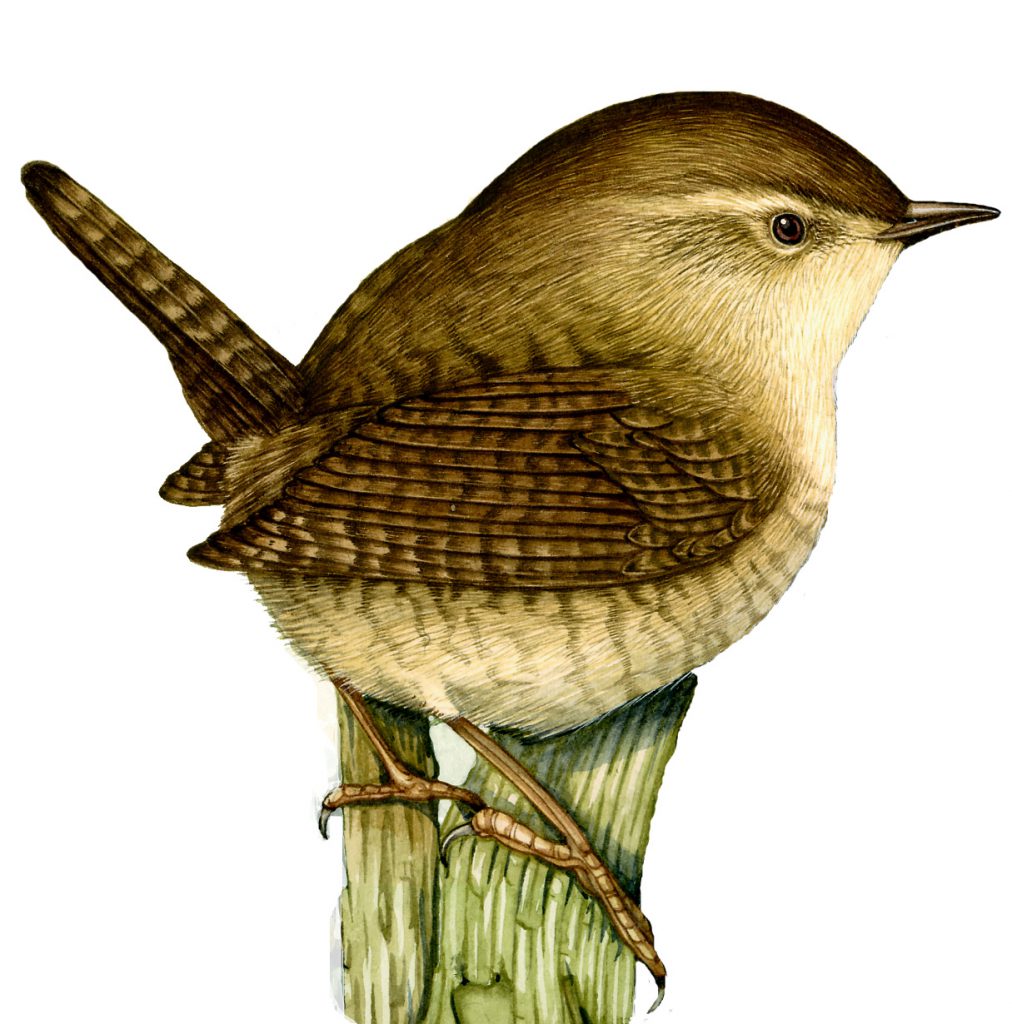

My illustration of the Wren

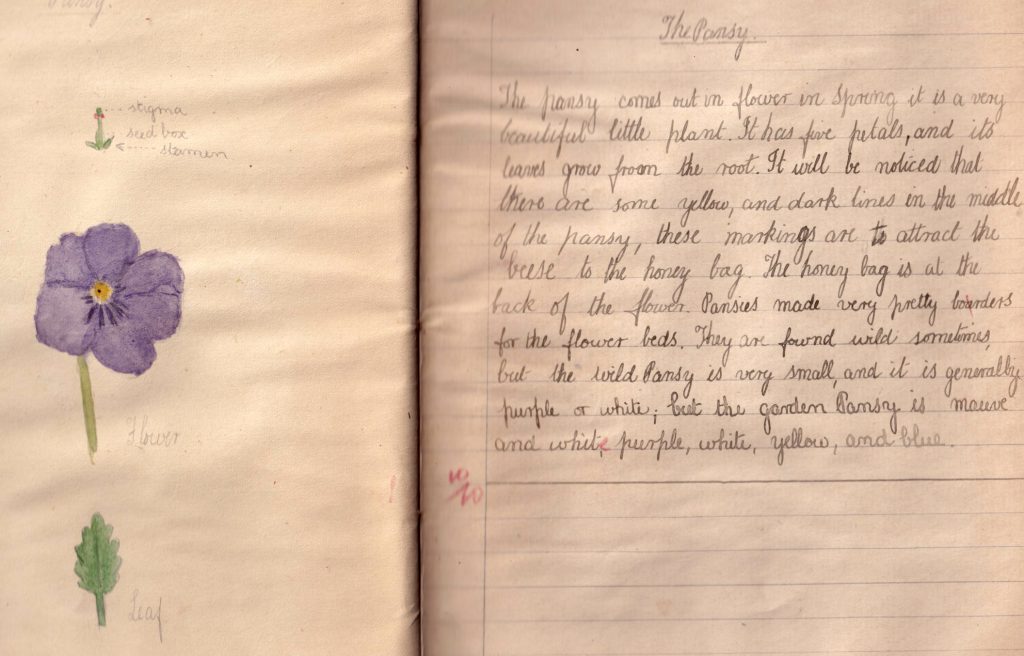

Although there are many more entries in Aunty Nina’s Nature notebook, the last one I’m looking at is a botanical subject; the pansy. By the way, if you want more blogs on her Nature notebook entries just say in the comments section, I’m more than happy to share more of them with you.

Nature Notebook: The Pansy

Not only do we get a ten year old’s watercolour of a pansy, but she has also recorded a typical leaf below the flower. Above, there’s a tiny labelled drawing showing the stigma, stamen, and swollen seed base. This reminds me of the way I work when I do my sketchbook studies, picking out aspects and drawing them separately from the main image.

Aunty Nina’s entry in the Nature Notebook on the Pansy

Her entry on the pansy reads, “The pansy comes out in flower in the spring. It is a very beautiful little plant. It has five petals, and its leaves grow from the root. It will be noticed that there are some yellow and dark lines in the middle of the pansy. These markings are to attract the bees to the honey bag [nectaries]. The honey bag is at the back of the flower. Pansies make very pretty borders for the flower beds. They are found wild sometimes, but the wild pansy is very small, and it is generally purple or white, but the garden pansy is mauve and white, purple, white, yellow, and blue.”

I love that she learned about nectaries. And I wonder if the red and orange culitvars we can get today had not been bred yet, back in 1919?

My illustration of a Pansy

As far as I know, Great Aunty Nina didn’t draw or paint as an adult. She was an incredibly glamorous figure in my youth. We only saw her occasionally as she had no interest in children. She only ever wore black and white, smoked from a long cigarette holder, had a short cropped hair cut, a collection of ex-husbands, and lived in Knightsbridge, London (and did her grocery shopping at Harrod’s. No. Really).

Nature Embroidery: My Maternal Grandmother

My maternal grandmother was a very arty lady. She not only did embroidery, but we also have a metal work box she made, and some watercolours. She embroidered lots of things; from greetings cards to sewing kits, napkins to dresses, needle cases to shoe bags (what even IS a shoe bag? And what would possess you to embroider one?). I love her embroidery, and treasure the few pieces I own.

Embroidery by my Grandmother

Most of her work is like the example above. Collections of beautifully observed wildflowers, easily recognizable to species level. In the piece above there are hazel catkins, Germander speedwell, marsh forget me not, yarrow, and red clover, to name a few. I think it’s the botanical accuracy along with the details that make me love her work so much.

Detail of one of my illustrations of meadow flowers

I adored my Grandmother, she was all indulgence and softness. Although she was surrounded by her embroideries, I never really took stock of the fact that she had created so much art until long after she died. I wish I’d told her how beautiful her work was.

Nature Collage: My Paternal Grandmother

My paternal grandmother was also artistic. She worked in oils and pastels, and was a consumate fine artist. Portraits, landscapes, and still lives were her main fare. However, when we were growing up, we had this extraordinary 3D collage by her hanging in our bedroom

3D Sewn collage of a Hoverfly by my Grandmother

The fact that her chosen subject is a hoverfly, rather than a butterfly or traditionally appealing insect makes me warm to her. The abdomen is made of fine velvet. the wings are net. Compound eyes are made of wooden beads. The ocelli (I love that these are included!) are embroidered onto the leather of the head. This is clearly a piece completed by someone with a love of, and respect for insects.

Hoverfly and bee with Japanese Knot weed blossom

I didn’t get on well with my Grandma, I was too irritating and she was perhaps a little too stern. I often wish that she had lived longer; she died when I was 12. As adults, we would have had so much to discuss, and doubtless would have got on wonderfully. We might even have gone on painting trips together!

Nature Still Lives: My mum

Many people who know me personally already know what an excellent artist my mother was. She is still with us, but unfortunately Alzheimer’s has taken away her pleasure in, and ability to draw; something that I mourn intensely. This is also why, when I talk about mum as an artist, even though I try not to I often find I use the past tense.

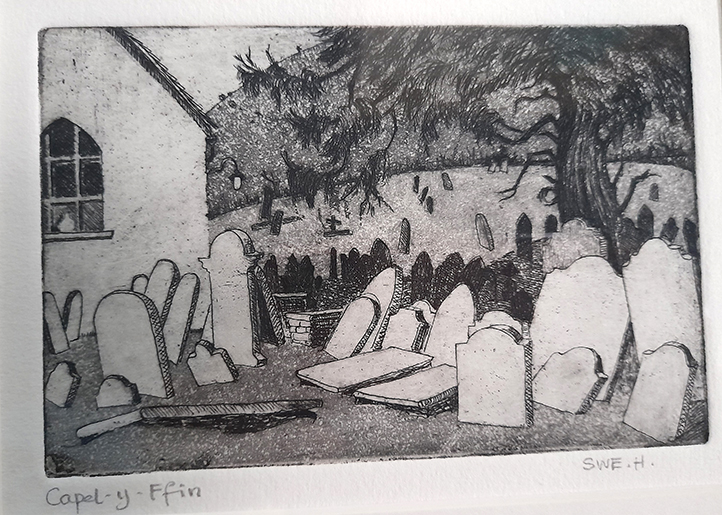

Mum’s etching of the graveyard at Capel Y Ffin

Mum was always drawing, all through my childhood. Piles of sketchbooks, etchings, life drawings, watercolours, painted furniture, lino cuts… She was prolific and extremely able. Mum’s favourite subjects are graveyards, American trucks, still lives of all white or all black crockery (the whites done on white paper, the blacks on black cartridge), cats, and thorn trees. She exhibited widely as Susan Wedgewood Harper, and has a series of 12 architectural watercolours in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC (where we lived for 10 years). She also illustrated books on cultural artifacts, designed logos for friends, and was a scene painter in Paris and Rome in her twenties.

Iris by my Mum

There’s more fluidity and movement to mum’s work than I see in my own, it’s something I’d like to work on. Below is my Iris, Iris reticulata.

Mum did still lives of plants that interested her. I love these, and wonder if her passion for the natural world, and her visual sensibilities helped inform my identify. I don’t see how it can’t have done! I think it’s the shape and colour that moved her, rather than the minute details, and there we differ a little. Her compositional eye is excellent, as is her watercolour technique.

Pineapple by Susan Wedgewood Harper (mum)

The Future generations…?

It’s too early to know whether or not my children will take an interest in drawing, painting, or creating art. When they draw, they draw beautifully, but neither does it with a passion…yet.

However, both my beloved niece Molly Lewis, and adored nephew Frank Lewis are excellent draftsmen and artists. Molly has done an art history degree, and Frank is studying animation at college.

Still life with lemons by Molly Lewis

Frank has an excellent pen and ink style which I am extremely envious of. Saying that, neither of them has become obsessed by illustrating natural objects. I’d love to see what they could do with a clump of moss, or a beetle. Perhaps I should commission them and see what they create?

Leaping person by Frank Lewis

Nature or nurture?

So here’s the question. Is this ability to draw innate, a natural “talent” that can be inherited? I’m afraid I don’t think so. I feel it’s rather more complicated than that.

If you grow up in a house where drawing is considered as important as reading and writing and maths, then you learn to draw as a child. It’s another language that becomes available to you. The more you draw, the better you get at drawing. Having an artistic parent means the house will probably be full of art materials, and you’ll be encouraged to create.

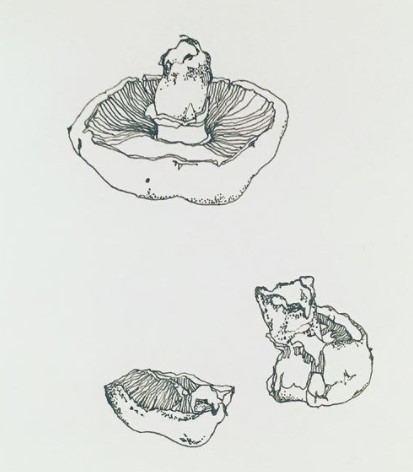

Line drawing of a mushroom by Molly Lewis

There’s also a big positive feedback loop going on here, too. This relates to families of artists, and to individuals. I like to draw. I draw. I get better at drawing. I like drawing even more. I get even better at drawing….

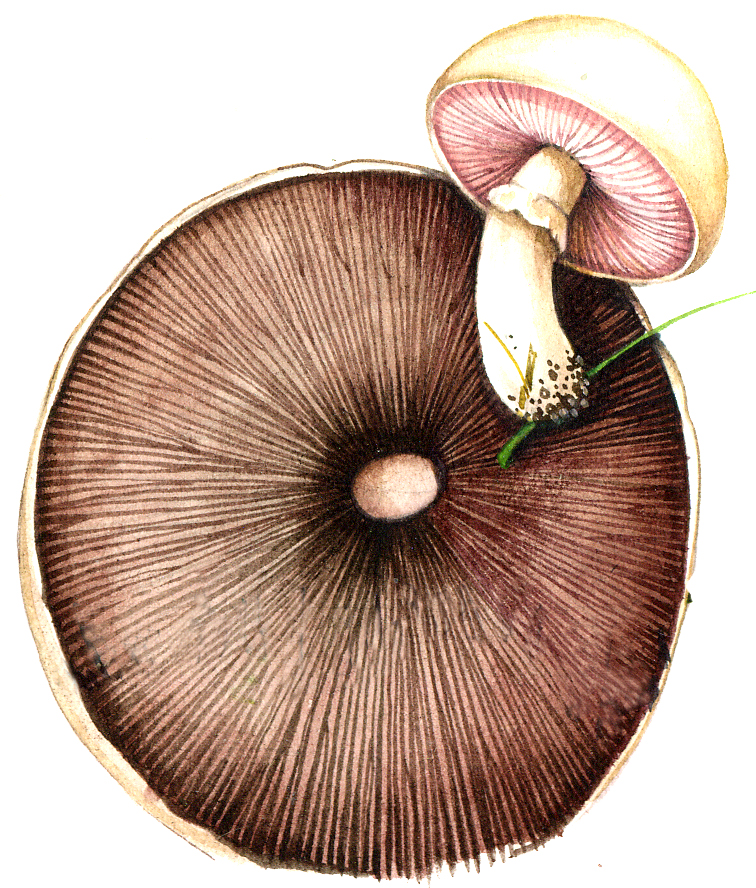

Mushroom watercolour by Susan Wedgewood Harper

I’m not saying there’s no such thing as talent. But I do believe that the way to get good at drawing is the same as everything else – practice. And if you are raised in an environment where drawing is actively encouraged, and you see it happening all the time… it’s almost a self fufilling prophesy.

Field mushroom Agaricus campestris by yours truly

In homes where parents and carers are not engaged in creating art, you still get children (then adults) who are exceptionally able at drawing and painting. This is another indication that “being good at art” is almost certainly not a genetic predisposition. It simply suggests these youngsters have been encouraged to keep doing what they love, despite their adults not sharing their passion.

Take home message for adults looking after kids? Always encourage your children to draw and paint. Make art materials easily and readily accessible, if you can. Be positive about their work. And then you too may have a “talented” artist on your hands.

The post Nature Notebook & The Family Tree appeared first on Lizzie Harper.