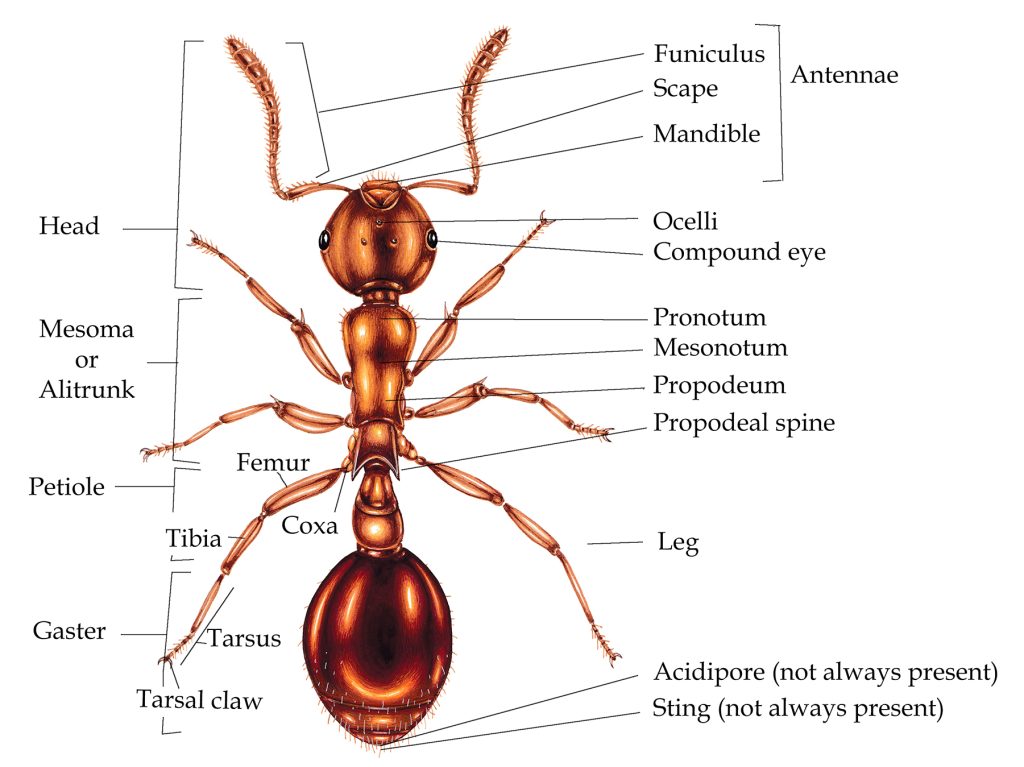

Having recently written a blog on the anatomy of ants, and been on three marvellous FSC courses about these fabulous insects, I’m going to try and share what I’ve learned about telling the four UK subfamilies of ants apart.

To get anywhere with ant identification, you need a basic grasp of ant anatomy, and a good dissecting microscope, as well as an expert on hand to set you straight when you get it wrong. Luckily for me, I had all three when I attended the FSC Biolinks Ant Identification with microscopes course in May, and a similar course just this week.

The line drawings in this blog were done at the course, using preserved specimens and microscopes.

Ant anatomy: Recap

So the parts of the ant anatomy that really matter when trying to sort out UK ant species are the petioles, how hairy the head and mesothorax is, whether you can see an acidopore or sting, and whether or not there’s a constriction between the segments of the gaster.

Ant anatomy using the Shining Guest ant Formicoxenus nitidulus

British ants

We’re lucky that telling ants apart in the UK is, in anting terms, comparatively simple. Although there are 21 ant subfamilies globally, we only have 4 to tackle. If you think that makes it an easy task though, think again!

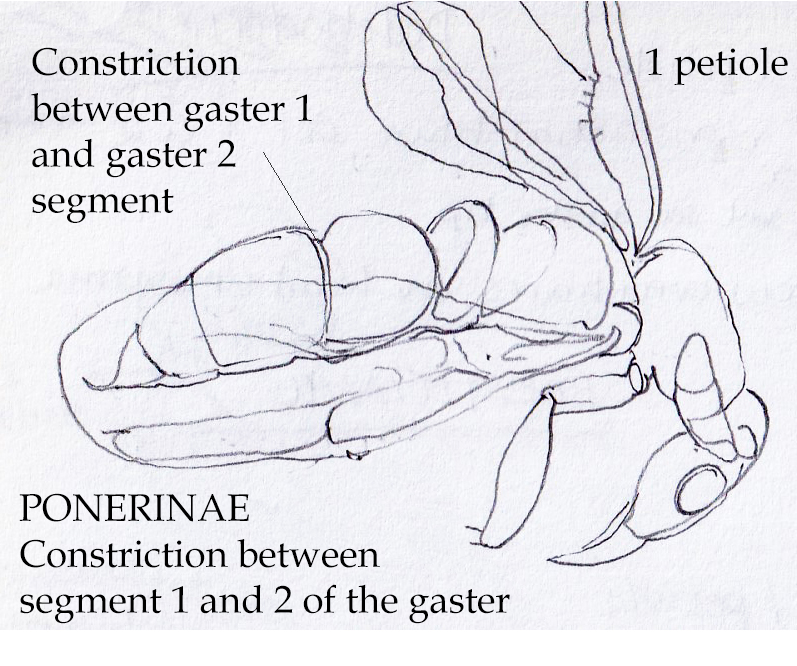

Ponerinae

The first subfamily is Ponerinae. These are possibly the easiest to spot. All Ponerinaes have a constriction between the first and second segment of their gaster. It looks like they’ve got a rubber band around them. They are stinging ants, and have one petiole.

This one happens to be a queen, so has wings.

The raised central area is the petiole. The gastral constriction is really clear, and was equally obvious in all the Ponerinae specimens I got to examine.

One of the largest ants on earth belong to this subfamily, Dinoponera gigantea. Indian jumping ants, Harpegnathos saltator are also Ponerines. In some cases, mated workers lay eggs, replacing the queen. There can also be male as well as female workers. these can be told apart by counting the antennal segments of the funiculus.

According to Antmaps, there are two native species in the UK, namely Ponera coarctata and Ponera testacea

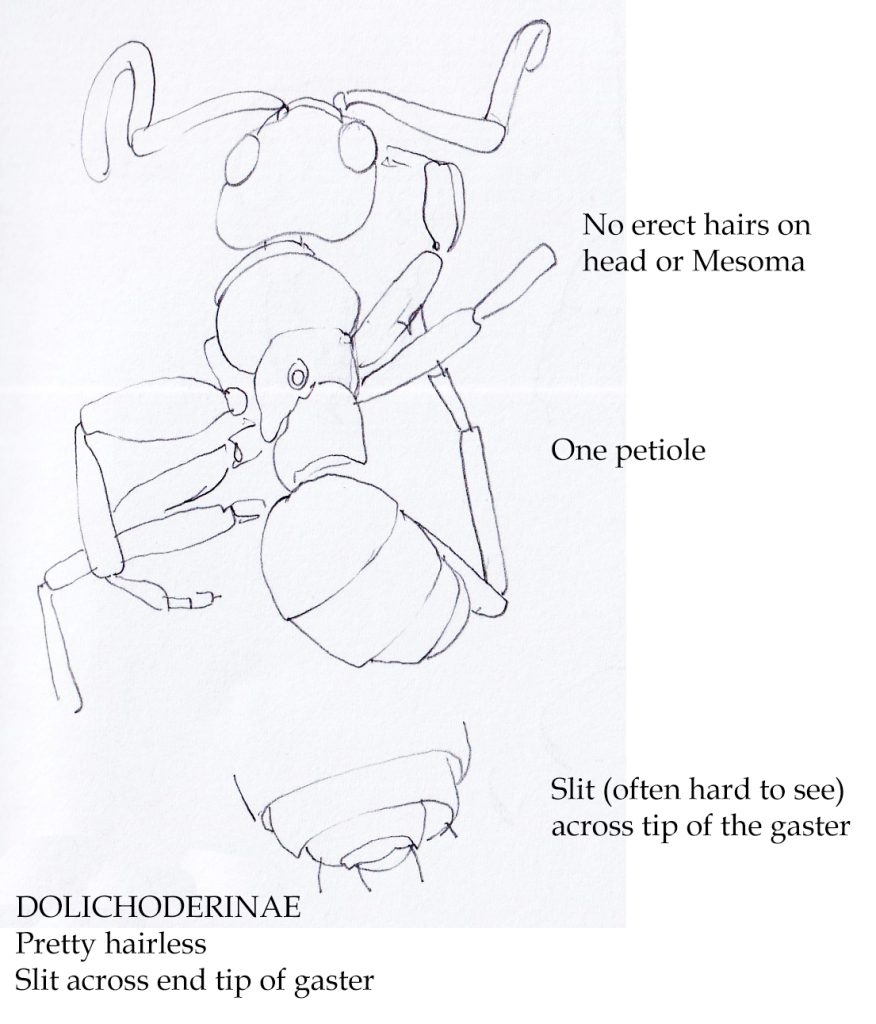

Dolichoderinae

Dolichoderinae don’t have any constriction of the gaster. They have one petiole. Unlike other ants, they have very few (and mostly no) erect hairs on the head or mesoma.

Specific to this subfamily is the presence of a slit-like acidopore. This replaces the sting, and is used to spray formic acid for defense, from the anal gland. this can smell quite unpleasant and strong.

It’s often ants in this subfamily who “farm” aphids for their honeydew.

Sketch of a Dolichoderinae, showing hairless head and thorax, one petiole, and acidopore slit.

A few species in this subfamily invade other ant nests, replacing the queen and enslaving the colony.

The most notorious of invasive ants, the Argentine ant Linepithema humile belongs to this subfamily. This species is seriously successful, outcompeting native species. It is not only found in South America, but in 6 continents across Australasia, Europe, North America, Asia and Africa; and in over 150 countries. It’s possible the places it hasn’t been recorded are due to lack of ant recorders rather than to the Argentine ant not being present there! All the ants in these colonies are genetically identical. And this spread only began 100 years ago. Thanks to (you guessed it) mankind’s endless traversal of the globe.

The two UK species in this subfamily listed by Antmaps are Tapinoma erraticum and Tapinoma subboreale.

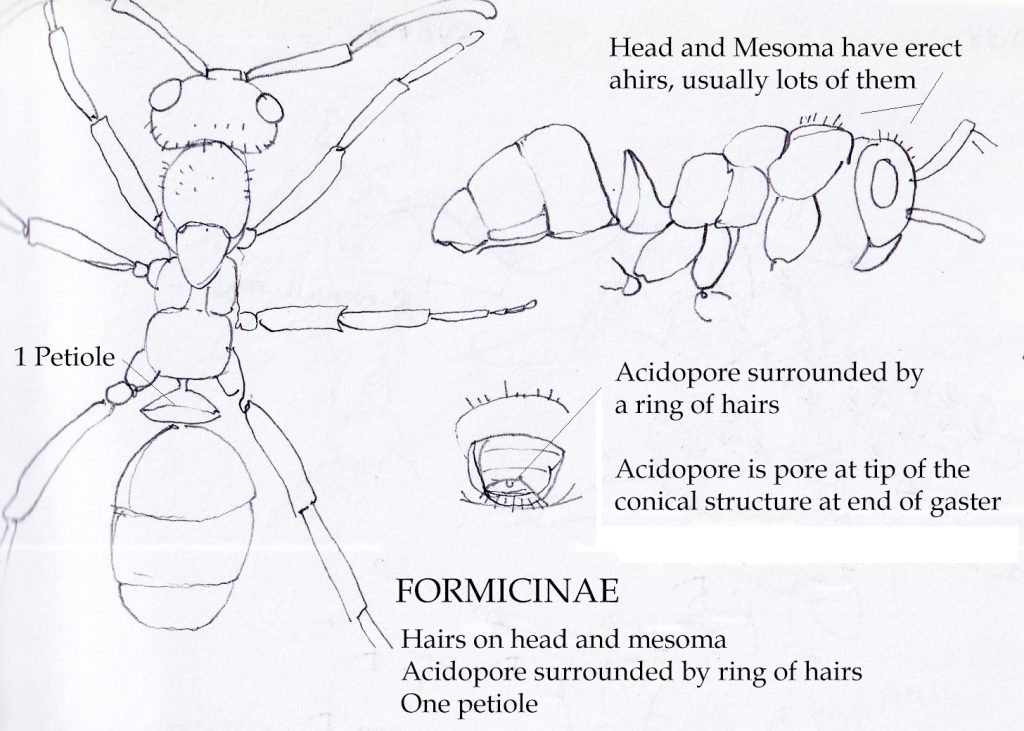

Formicinae

You can tell a Formicinae ant with the following list: most have erect hairs on their heads and mesosoma, they have no gastral constrictions, they have one petiole, and a round (not slit shaped) acidopore, and the acidopore is surrounded by a collar of hairs.

This is a successful and diverse group, with over 3,600 species described.

So are the Wood ants, which I illustrated back in 2021.

Illustration of Formica rufibarbis showing the round acidopore, hairs on head and mesosoma, and single petiole

Honeypot ants, Carpenter ants, and Weaver ants are all members of this subfamily. Honeypot ants Myrmecocystus store sweet food in the swollen abdomens of their workers. Although many thought this was honey, it’s actually simple sugary nectar and honeydew from aphids.

Carpenter ants Camponotus build their nests underground or in rotting wood and are one of the most numerous of the ant genus.

Weaver ants Oecophylla live mainly in the tropics, and build nests by using the silk produced by their larvae, these are held in the jaws of the workers and used almost like glue guns, with the silk knitting complicated nests in the trees. One nest may hold as many as 500, 000 individual ants. They’re hunters, and take insect prey.

According to Antmaps, there are 24 native species in the UK, including all our wood ants.

Hairy wood ant Formica lugubris alongside specimen

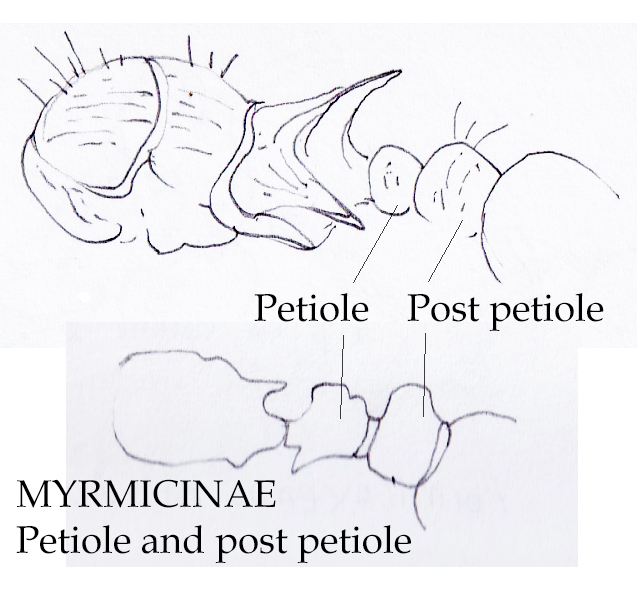

Myrmicinae

Myrmicinae ants are almost as easy to spot as Ponerinaes. Their distinguishing feature is a two-part petiole. There’s a petiole…and another one known as the Post petiole. These may be hidden under the Proprodial spine, but once you get your eye in it’s an instant indicator.

These ant species can vary from 1mm to 10mm in length, and highly varied. They’re probably the most numerous of the subfamilies with over 6,700 species identified.

This illustration shows a close up of the Petiole and post petiole of Myrmica ruginodis

I got to draw two of these in the workshop; Myrmica rubra, M. ruginodis.

Nests of Myrmicinae tend to be comparatively small, with only a few hundred of thousand workers. As always though, there are exceptions to this. The Acorn ant Temnothorax nylanderi is a tiny species and an entire colony can exist within one acorn.

According to Antmaps, there are 23 native species in the UK, including my favourite, the Shining Guest ant Formicoxenus nitidulus.

Myrmicinae Shining Guest ant Formicoxenus nitidulus

Conclusion

Hopefully this dive into the four ant subfamilies in the UK has been interesting. For more on ants, do check out my blog on illustrating the wood ants of the Cairngorms, and an introduction to ant anatomy.

My obsession with ants is continuing. I have now learnt how to identify a few down to species level, and have signed up for another ant course (the 4th this year!), this time a three day residential course. I’m hoping to be able to recognize even more species by the end, and to start feeling confident with ants and keying them out to species level. None of this would be possible without the knowledge of the tutors I’ve met, and the courses offered by FSC.

I’m far from being an expert, so if you spot a mistake please let me know and Ill do my best to fix it as soon as I can.

The post Ants in the UK: Four subfamilies appeared first on Lizzie Harper.