James Archer is a medical illustrator and animator who combines artistic imagination with science through striking images that captivate and educate his audience. With a background in Biology and Art History, James has worked for a variety of notable organizations like WebMD, the CDC (Center for Disease Control) and the National Library of Medicine.

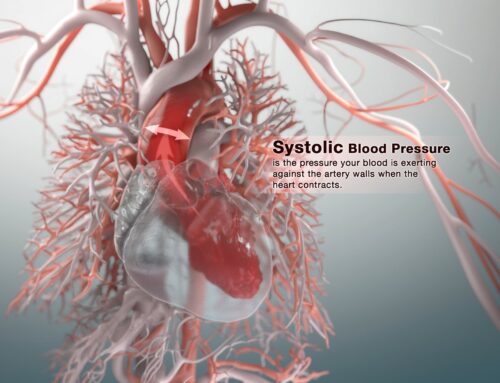

During his time at the National Library of Medicine he was deeply immersed in 3d software and rendering technology. It was then that he began developing his lighting and texturing techniques for what would soon become Anatomy Blue.

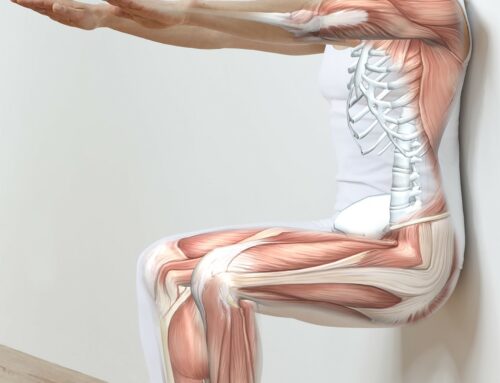

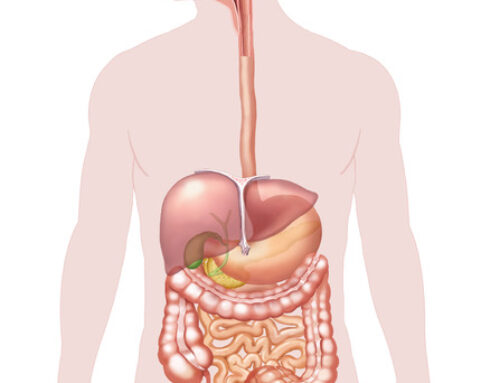

Anatomy Blue specializes in the creation of didactic and cinematic imagery for the pharmaceutical, health care, and publishing communities. Services include editorial, medical, scientific, and technical illustration and animation.

James has been a Medical Illustration Sourcebook advertiser since 2004. We caught up with him last week to find out more about his influences, background, and Anatomy Blue.

What led you to a career in medical illustration? Were you the kid drawing skulls and skeletons in the margins of your schoolwork?

Close, I was the kid drawing dinosaurs and alien planets in the margins of my schoolwork. I was really into fantasy, sci-fi, and dinosaurs as a kid. It wasn’t until my middle school years that I started drawing from life. I would setup a still life in my room or sit outside and draw whatever caught my eye.

In my high school years I learned about the field of medical illustration. My mother, a radiology tech at Emory University Hospital at the time, told me about the hospital’s on-staff medical illustrators. Although I never got the opportunity to drop by the illustration department for a visit, after learning more about the field I knew then exactly what I wanted to pursue in life.

You worked for some pretty prominent medical education organizations before you launched Anatomy Blue in 2002. Tell us what was most valuable about your corporate and public health experience, and why you decided to strike out on your own?

You’re right, I’ve been very fortunate to have worked at many prominent organizations: EAI (Engineering Animation, Inc.), Nucleus Medical Media, WebMD, NLM (National Library of Medicine) and CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). I think the most valuable lessons anyone can learn from working in large organizations like these are lessons related to customer service. When competing in a field of super talented individuals, sometimes great customer service can set you apart. Realize that your clients are often working under extreme pressures; do everything in your power to make them feel that their every need is being met and that your project is the last thing they need to worry about.

Anatomy Blue is my attempt to chase my own curiosities and obsessions as an illustrator. Every illustrator answers to someone regardless of where you work, be it the home office or the corporate office. But as a freelance illustrator, I’ve always experienced a certain sense of excitement and nervous anxiety that comes with every new project. And the best part is knowing that I am solely responsible for finding solutions every step of the way. There’s no one there to back me up if I don’t have the answers. It’s actually quite liberating.

When you started your company, how did you determine which direction you would take as an independent artist? How did you build your business and what type of clients did you target, and ultimately attract?

I found my direction as an artist with help from the Medical Illustration Sourcebook. In the early days of Anatomy Blue I was looking for a niche, a place in the market where I could compete while avoiding the starving artist cliché. I would flip through the Source Book, land on a page, and ask, can I compete with this artist at their game? After taking one look at John Daugherty’s page I knew that I would never beat this guy at his game – trust me, he’s good. It was an exercise in coming to terms with my own limitations as an artist and discovering the one thing that I enjoy doing most, the one thing that I was damn good at. For me, that one thing was 3D illustration and animation.

I would like to tell you that I intentionally targeted specific clients in the beginning; it just wasn’t the case. I absolutely had no plan of attack but I knew one thing for sure, medical illustrators advertise in the Sourcebook. That simple. And by following suit, what I discovered was that clients found me. At first it was magazines, then ad agencies, and then things just sort of snowballed. I think it was the use of photographic and cinematic rendering techniques that drew clients to my work. In the end I was just doing what I loved and with help from the Sourcebook, the market responded.

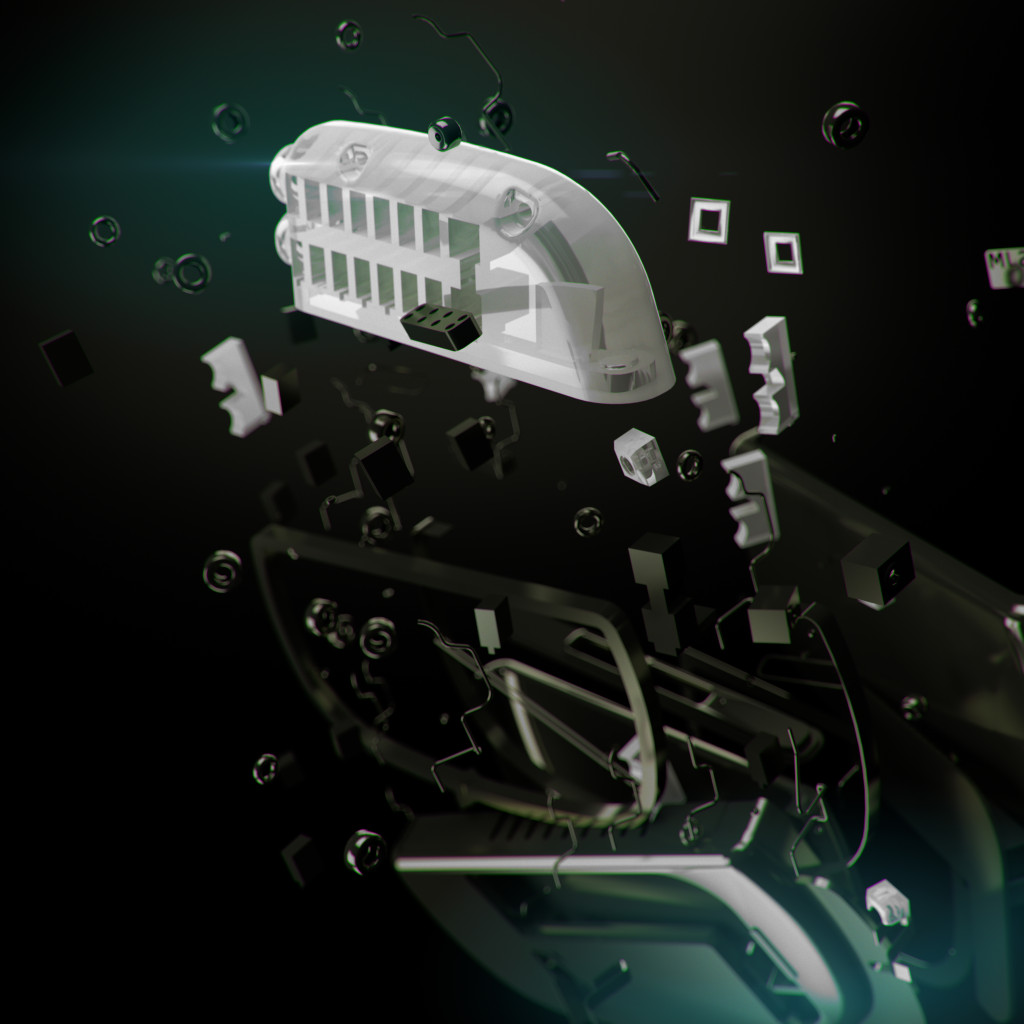

Scientific visualization combines hard science with artistic imagination. Your job is to communicate abstract concepts that occur on a molecular level. How do you decide what that teeny, tiny world looks like? And how do you translate that story to the rest of us who can’t see what you see?

It’s an excellent question. It reminds me of a discussion regarding Chuck Jones, Bugs Bunny, and realism. We all know what a rabbit looks like and for the most part, Bugs Bunny doesn’t look anything like a “real” rabbit. But Bugs looks believable, so much so that many will suspend their disbelief and get drawn into his crazy universe. In short, “the more effort that is put into suspending the

When representing tiny worlds like the one you’ve described I will often use techniques that mimic physical materials and physical phenomena found in macro photography. More specifically, I will use sub-surface scattering materials, a narrow depth of field, chromatic aberration, lens flares, and the likes. In all, it helps to make the image look authentic.

How much of your work is 3D illustration and how much is animation? What type of projects do you enjoy the most?

It’s about 70/30, illustration vs. animation. I use the same software and production techniques for each so the experience is essentially the same. I would say that animation projects tend to have longer production timelines but there are always exceptions. I recently created two cinematic animations for an ad agency, each in under three weeks, VO and sound design included. It was totally crazy but we made it happen.

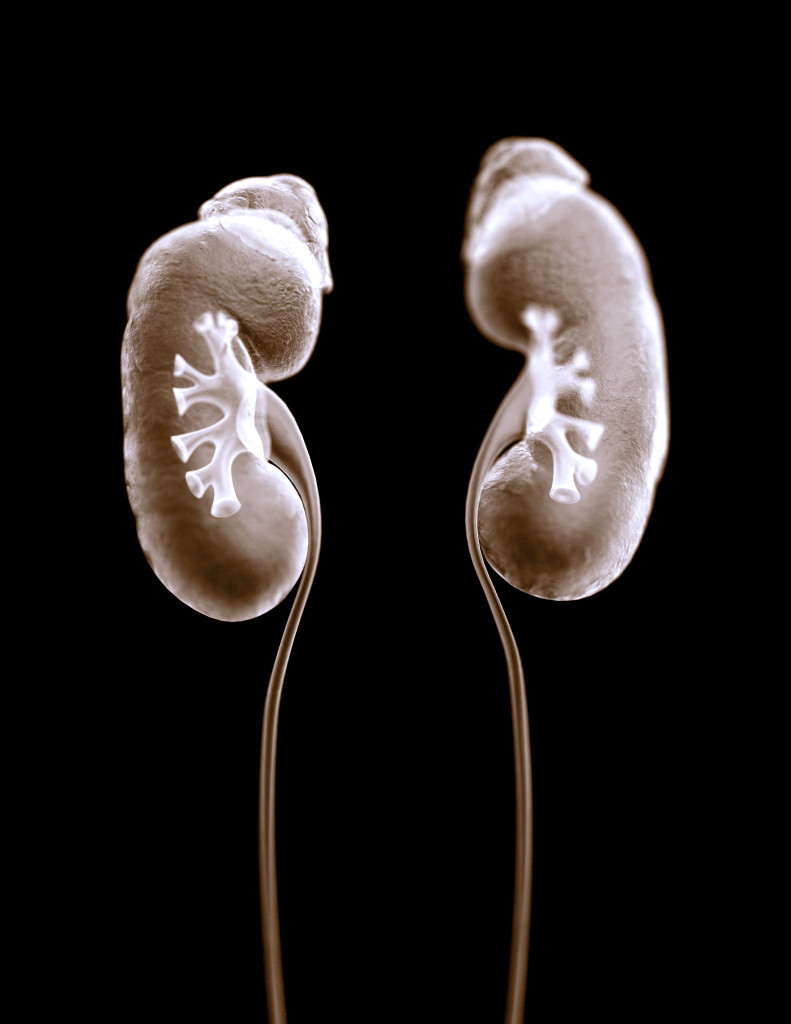

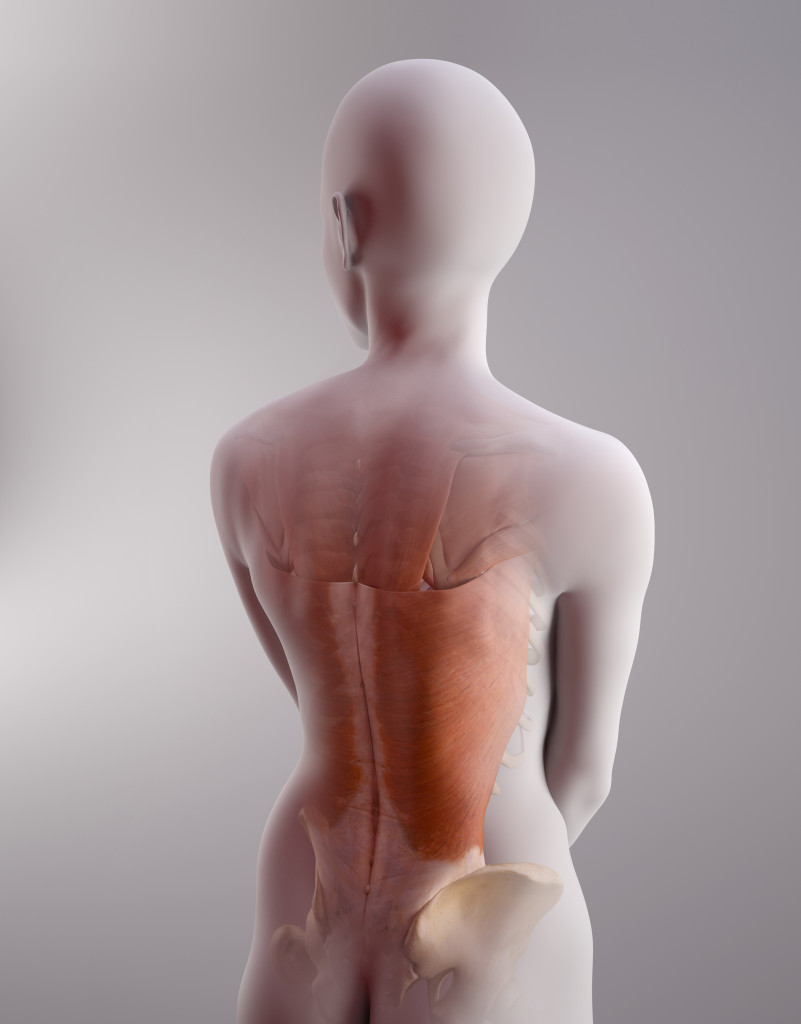

Your images have a purity and simplicity that sometimes feels more like fine art photography than commercial illustration. They instruct and communicate on a very emotional level, yet they are grounded in reality. You use a very soft, monochromatic palette that is very different than others in your field, which makes them stand out and contributes to the power of the images. How did you come to develop this style?

It all started at NLM where I worked in research and development. My job was essentially to test new hardware, software, and production techniques and to provide advice as needed. My focus was on 3D animation as it applied to HD video. I would spend days investigating new software features, testing lights and materials, and keeping our render farm warm and toasty. Over time I began to develop light rigs, material libraries, and studio setups. Studio setups are essentially 3D scenes modeled after real photography studios. These virtual studios allowed me to test various shaders and materials in an exposure controlled environment with physically accurate lights and cameras.

So as you can see, my style is deeply rooted in photography – sort of. As for color choice, I find that it’s much easier to create lifelike images with conservative color palettes. Some of my most referenced pieces, like Aspergillus and Brain, have a very narrow range of color. I agree, it sometimes feels more like photography than illustration. And like black and white photography, I think that a soft monochromatic palette has a way of evoking an emotional response that would otherwise be difficult to achieve using a kaleidoscope of color.

What inspires you and gives you direction for your future?

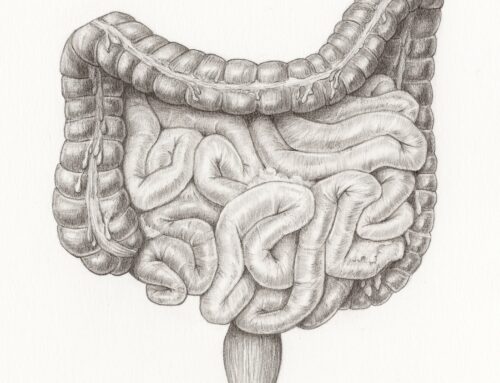

I find most of my inspiration in macro nature photography. I’m also obsessed with synthesis – in a dialectical sense, the combination of two seeming different ideas to create something new and different. I recently came across a macro photo of sand. I know, right … sand. But when I looked at the photo I thought that the surface quality of the sand could easily pass as the surface of a lipid bilayer. I used that photo as the basis for my modeling, texturing and lighting. It was the combination of these two ideas, sand + bilayer, that resulted in a really nice image.

What advice would you give to someone considering 3D medical animation as a career?

Regardless of the path you choose, choose it because you love it; that would be my best advice. I once had the opportunity to visit Hurd Studios back in the day. A colleague and I dropped by around seven or eight on a Friday evening. To my surprise there were maybe four or five animators still working. Keep in mind, there’s a reason why places like Pixar have kitchens, free food, gyms, showers, places to rest … 3D animation is not easy work. It can take a long time to deliver on a project.

If you weren’t a medical illustrator/animator, what would you be?

Biologist … herpetologist … something along those lines. I don’t think I would have survived in the field of fine art. Taking a coastal biology and herpetology class at Emory really changed my view of the world around me. Now I can’t walk through a patch of woods without looking under a fallen log to see what’s hiding underneath.